When you pick up a prescription, you might not think about why your insurance covers one version of a drug but not another. But behind every pill bottle is a complex system designed to save money - and it’s called a preferred generic list. These lists aren’t random. They’re carefully built by teams of doctors and pharmacists, and they shape what medications you can get, how much you pay, and sometimes even whether your doctor can prescribe what they think is best.

What Exactly Is a Preferred Generic List?

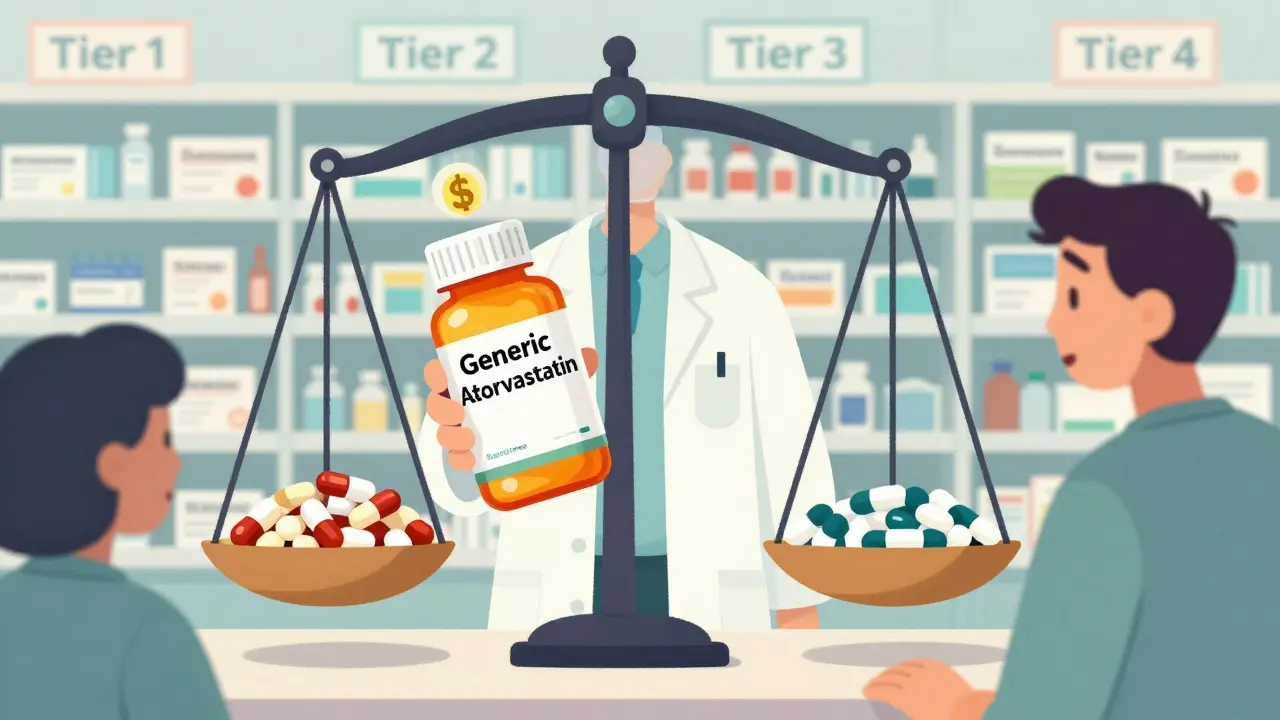

A preferred generic list is part of an insurance plan’s formulary - a ranked list of drugs the plan will cover. It’s divided into tiers, and Tier 1 is where the preferred generics live. These are FDA-approved copies of brand-name drugs that work the same way but cost 80-85% less. For example, the brand-name drug Lipitor (atorvastatin) for cholesterol has dozens of generic versions. Insurers push those generics hard because they’re just as effective and way cheaper. The system started taking shape in the late 1990s with the rise of Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs), companies that negotiate drug prices for insurers. By the time Medicare Part D launched in 2006, tiered formularies were standard. Today, 100% of Medicare Part D plans and 98% of commercial plans use them. That means if you’re insured in the U.S., your drug coverage is almost certainly shaped by this system.How the Tiers Work - And Why It Matters to You

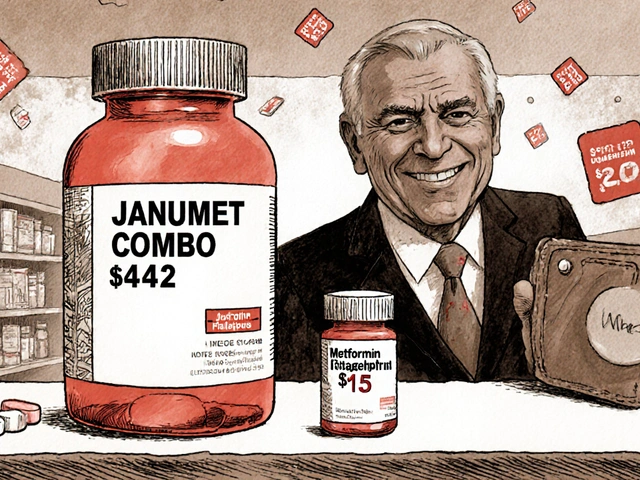

Most formularies have four or five tiers. Each one changes how much you pay at the pharmacy.- Tier 1: Preferred generics - These are the cheapest. Copays are usually $5-$15 for a 30-day supply. Think metformin for diabetes, lisinopril for high blood pressure, or levothyroxine for thyroid issues.

- Tier 2: Preferred brand-name drugs and some higher-cost generics - Copays jump to $25-$50. These are drugs insurers still cover but don’t push as hard because they’re pricier.

- Tier 3: Non-preferred brand-name drugs - You’ll pay $50-$100. Your insurer doesn’t like these. You might need prior authorization just to get them.

- Tier 4: Specialty drugs - These are biologics, cancer drugs, or rare disease treatments. Costs can be $100+ per month, or you might pay a percentage of the price (coinsurance). Humira, for example, can cost over $1,200 a month - but its biosimilar Amjevita is around $850.

Why Insurers Push Generics - The Numbers Don’t Lie

It’s not just about saving a few dollars. It’s about billions. In 2023, generic drugs made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they accounted for only 23% of total drug spending. That’s the power of scale and competition. When six or more companies make the same generic, prices can drop up to 95%. PBMs negotiate directly with manufacturers. For brand-name drugs, they get 25-30% rebates. But for generics? They buy in bulk at wholesale prices. That’s why a 30-day supply of generic atorvastatin can cost $4 at Walmart - and your insurer pays even less. The savings add up fast. A 2022 study found that switching from brand to generic saved patients an average of $194 per prescription. Multiply that by hundreds of millions of prescriptions, and you get $1.68 trillion saved annually for the whole system.Where the System Falls Short - Biosimilars and Patient Struggles

Not all drugs play nice with this model. Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - are the exception. Their generic versions are called biosimilars. They’re cheaper, but not as cheap as traditional generics. And here’s the catch: brand-name biologic makers often offer co-pay cards that cut your monthly bill to $0. Biosimilar makers? They rarely do. That’s why patients on Humira might pay $1,200 a month, but switch to Amjevita and still pay $850 - because they lose their co-pay card. The savings are real on paper, but not always in their wallet. In 2023, only 15% of eligible biologic prescriptions switched to biosimilars in the U.S. Compare that to Europe, where it’s 85%. Another problem: step therapy. Some insurers make you try the generic first - even if your doctor says it won’t work for you. If you fail, then you can move up to the brand. But failing can mean weeks of uncontrolled pain, high blood pressure, or worsening diabetes. A 2022 AMA survey found 42% of physicians reported delays in treatment because of this.What Patients Can Do - And How to Save

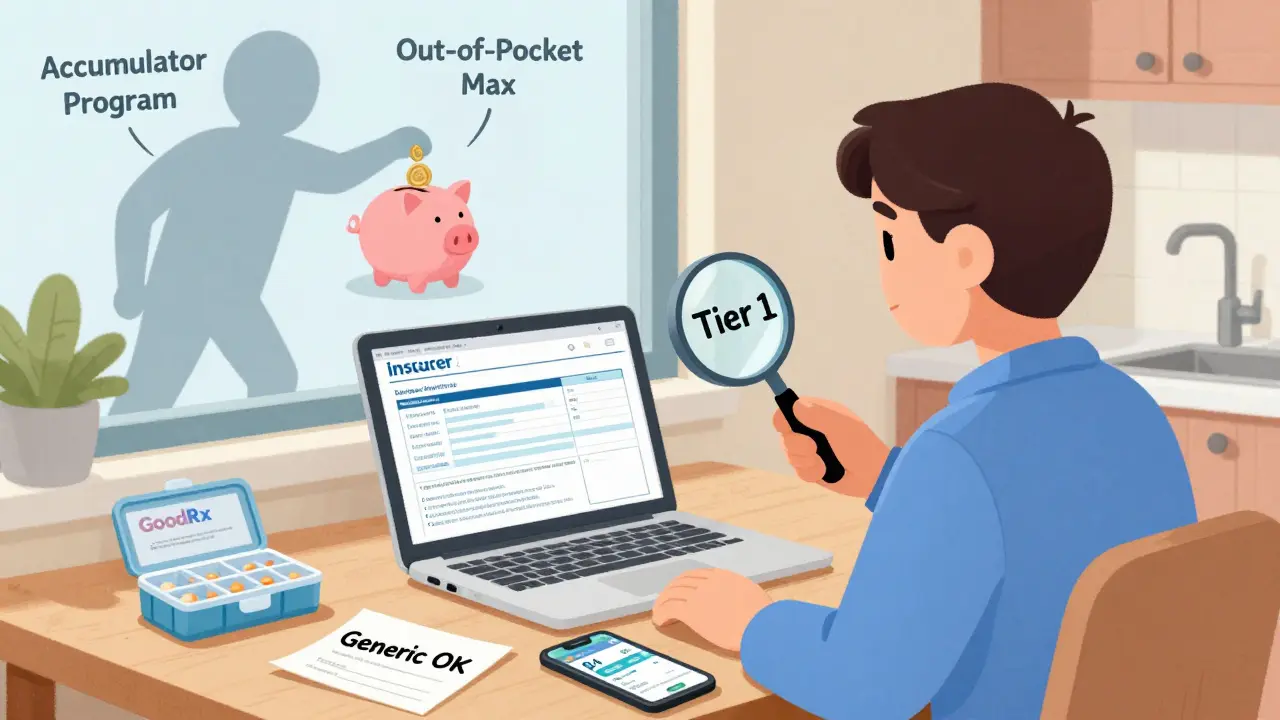

You don’t have to just accept the formulary. You have power.- Check your formulary during open enrollment. Every year, insurers change which drugs are preferred. A drug that was Tier 1 last year might be Tier 3 this year. Use tools like Medicare’s Plan Finder - it scores 4.2/5 for usability. Commercial plans? They average 2.8/5. Don’t trust them.

- Ask your pharmacist. In 89% of states, pharmacists can swap a brand for a generic unless your doctor writes “dispense as written.” Most patients don’t know this. Ask: “Is there a generic version?”

- Appeal if denied. If your doctor says you need a non-preferred drug, file an exception. In 68% of cases, insurers approve these appeals - if you have solid medical documentation.

- Use GoodRx or SingleCare. Sometimes the cash price at CVS is lower than your insurance copay. Compare before you pay.

The Bigger Picture - What’s Changing in 2025

The system is evolving. Starting in 2025, Medicare Part D plans must place biosimilars in the same tier as their brand-name counterparts. That’s a big deal. It could push biosimilar use from 15% to 45% in just a few years. UnitedHealthcare is already testing “value-based formularies” - where tier placement isn’t just about price, but real-world results. If a generic works better for people with diabetes, it moves up. That’s a shift from cost-only thinking to outcome-based decisions. But there’s a dark side: accumulator adjuster programs. Some PBMs now count your co-pay card savings as “not real” when calculating your out-of-pocket maximum. So even if you’re paying $0 thanks to a card, it doesn’t count toward hitting your $2,000 cap in 2025. That means you might pay more later.Final Thought: It’s Not About Controlling You - It’s About Controlling Costs

Insurers aren’t trying to be mean. They’re trying to keep premiums low. And generics are the single most effective tool they have. The system works brilliantly for statins, blood pressure meds, and antidepressants - where hundreds of safe, cheap generics exist. But it stumbles when it comes to complex drugs, patient-specific needs, and financial protections. The real issue isn’t the list itself - it’s the lack of transparency and flexibility. Patients deserve to know why a drug is preferred. Doctors deserve to be heard. And everyone deserves to pay what’s fair - not what the algorithm says. If you’re on a chronic medication, take 20 minutes this month. Look up your drug on your insurer’s formulary. Call your pharmacist. Ask your doctor if a generic is safe for you. You might not save $1,000 - but you might save $100 a month. And that’s not nothing.Why do insurance companies prefer generic drugs?

Insurance companies prefer generic drugs because they’re FDA-approved copies of brand-name drugs that work the same way but cost 80-85% less. When multiple companies make the same generic, prices drop even further - sometimes by 95%. This helps insurers keep premiums low and reduces overall healthcare spending. For example, a 30-day supply of generic atorvastatin can cost under $5, while the brand-name version (Lipitor) might cost $150.

What is a formulary tier?

A formulary tier is a level in an insurance plan’s drug list that determines how much you pay. Tier 1 includes preferred generics with the lowest copays (usually $5-$15). Tier 2 has preferred brand-name drugs and some generics ($25-$50). Tier 3 is for non-preferred brands ($50-$100), and Tier 4 is for expensive specialty drugs, often requiring coinsurance or prior authorization.

Can I still get a brand-name drug if it’s not on the preferred list?

Yes, but it’s harder. You’ll pay more - often $50 to $100 or more per prescription. Your doctor may need to file a prior authorization, explaining why the generic won’t work for you. If approved, you’ll get the brand. If denied, you can appeal. About 68% of appeals are approved with proper medical documentation.

Why are biosimilars harder to get than regular generics?

Biosimilars are cheaper versions of complex biologic drugs, but they don’t come with co-pay assistance programs like the original brands do. For example, Humira might have a $0 co-pay card, but its biosimilar Amjevita doesn’t. So even though Amjevita costs less, your out-of-pocket might not drop much. Also, insurers don’t always place biosimilars in the lowest tier - though that’s changing in 2025.

How can I find out which tier my drug is on?

Log in to your insurer’s website and search for your plan’s formulary. Medicare beneficiaries can use the Plan Finder tool at Medicare.gov. Commercial plans vary in clarity - many are hard to navigate. If you can’t find it, call customer service and ask for the current formulary document. Pharmacists can also look it up for you.

Do pharmacists automatically switch my brand to a generic?

In 89% of U.S. states, pharmacists can substitute a generic for a brand-name drug unless the doctor writes “dispense as written” on the prescription. Many patients don’t know this. Always ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic version available?” Even if your doctor prescribed the brand, you might still get the cheaper generic unless they specifically blocked it.

Comments

I just asked my pharmacist for a generic and saved $80 this month 😊

Honestly I didn't even know formularies existed until my insulin got pulled from tier 1. Now I check mine every year. Wild.

This system isn't perfect, but it's not evil either. Insurers aren't out to get you-they're trying to keep costs down so people can actually afford coverage. The real villain is the lack of transparency. If we made formularies as easy to read as a McDonald's menu, everyone would win.

I come from India where generics are the norm and people still get great care. Here in the US, even though we have all this tech and money, we make it so complicated. I've seen friends cry over $100 copays for blood pressure meds that cost $4 in Delhi. It's not about the science-it's about who gets to decide what's affordable. Maybe we need to stop treating medicine like a stock market and start treating it like a human right.

The notion that PBMs are somehow altruistic is a delusion propagated by those who have never read a single line of a formulary contract. The tiered system is a predatory architecture designed to extract maximum profit under the veneer of cost-efficiency. One must understand that the term 'preferred generic' is a marketing construct, not a clinical one. The FDA does not certify preference; corporate actuaries do.

I checked my formulary last week. Turns out my antidepressant moved from Tier 1 to Tier 3. My doctor didn’t tell me. My pharmacist did. I had to appeal. Took three weeks. I’m still on the same dose. But now I know to ask before the script is even written.

My mom’s on Humira. We switched to Amjevita last year. Paid $800 instead of $1200. No co-pay card. But we saved $400/month. Worth it. Still wish they’d let us keep the card though.

pharmacists can swap your brand for generic unless doc says no you didnt know this youre not alone but now you know go ask next time

One must acknowledge that the structural inequities embedded within the American pharmaceutical ecosystem are not merely fiscal but epistemological. The formulary, as a regulatory artifact, privileges commodified efficiency over individualized therapeutic autonomy. The patient, in this paradigm, is reduced to a data point in a cost-benefit algorithm, their clinical narrative subordinated to actuarial logic. This is not healthcare-it is risk management dressed in white coats.

America makes the best drugs. Why are we giving them away to foreign generics? This is why we lost our edge.