When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the hope is that cheap generics will flood the market, driving prices down and giving patients affordable access. But in many cases, that’s not what happens. Instead, the same company that made the original drug launches its own authorized generic-identical in every way, just with a different label-right as the first independent generic enters. And suddenly, the promise of competition starts to unravel.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic is not a new drug. It’s the exact same pill, capsule, or injection as the branded version, just repackaged and sold under a generic name. No new clinical trials. No new FDA approval. The manufacturer simply takes its existing New Drug Application and adds a generic label. It’s legal. It’s allowed under the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. And it’s become a standard tool in the pharmaceutical industry’s playbook.Here’s how it works: A generic company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) and challenges the patent on the branded drug. If they win, they get 180 days of market exclusivity-the first generic to enter gets to be the only one on the market during that time. That’s the incentive. That’s the reward. But if the brand company decides to launch its own authorized generic during those 180 days, it doesn’t need to challenge the patent. It doesn’t need to wait. It just rolls out its version alongside the independent generic.

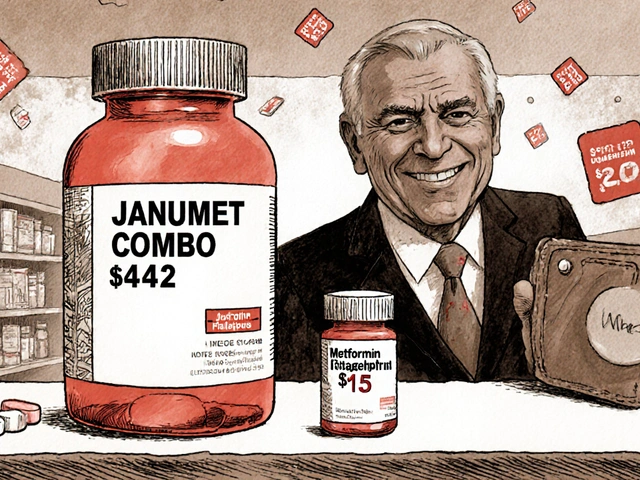

And here’s the catch: the authorized generic doesn’t come in at generic prices. It often sells for 15-20% less than the brand name, but 25-30% more than the independent generic. That creates a pricing sandwich. Patients and pharmacies get three options: the expensive brand, the mid-tier authorized generic, and the low-cost independent generic. But guess which one most buyers pick? The middle one. Because it’s still cheaper than the brand, and it’s still trusted-same manufacturer, same factory, same quality control.

How Authorized Generics Crush Independent Generic Competition

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has studied this for years. Their 2011 report found something shocking: when an authorized generic enters the market, it steals 25-35% of the generic market share from the first-filer generic company. That means instead of capturing 80-90% of the generic sales during their 180-day exclusivity window, the independent generic ends up with barely half.And the damage doesn’t stop after 180 days. The FTC found that in the 30 months after exclusivity ends, companies that faced authorized generic competition saw their generic revenues drop by 53-62%. That’s not a blip. That’s a financial earthquake. For a company like Teva, which reported a $275 million revenue shortfall from one authorized generic alone, this isn’t theoretical-it’s existential.

Why does this matter? Because the whole system of Hatch-Waxman is built on the idea that the first generic challenger gets a big reward: 180 days of monopoly pricing. That’s how they recoup the millions they spent on litigation. If that reward is gutted by the brand company’s own version, why would any generic firm risk a patent challenge in the first place?

According to the Congressional Research Service, for drugs with annual sales between $12 million and $27 million-smaller, but still profitable-expecting an authorized generic to enter can be enough to make a generic company walk away. They calculate the odds, see the revenue they’d lose, and decide it’s not worth the legal battle. That means fewer challenges. Fewer generics. Higher prices for longer.

The Secret Deals: When Brands Pay Generics to Stay Away

Sometimes, the authorized generic doesn’t even show up. Not because the brand doesn’t want to launch it-but because they’ve already made a deal.From 2004 to 2010, about 25% of patent settlements between brand and generic companies included an agreement: the brand promises not to launch an authorized generic, and in return, the generic agrees to delay its market entry. These are called "reverse payment" settlements. The brand pays the generic to stay off the market. And the authorized generic becomes the bargaining chip.

The FTC found these deals delayed generic entry by an average of 37.9 months. That’s more than three years of monopoly pricing. And the market value of drugs involved? Over $23 billion.

These arrangements are so damaging that the FTC has called them the "most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior" in pharma. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that reverse payments could violate antitrust laws-but it didn’t specifically ban authorized generic deals. That left a loophole. And for years, companies filled it.

But things are shifting. A 2023 study showed authorized generics are now significantly less likely to enter the market after patent settlements. Why? Because regulators are watching. The FTC has opened 17 investigations since 2020. In October 2022, FTC Director Holly Vedova said the agency will challenge any arrangement that uses authorized generics to "circumvent the competitive structure Congress established in Hatch-Waxman."

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

The brand companies argue they’re helping consumers by bringing down prices faster. Scott Gottlieb, former FDA commissioner, said authorized generics provide "immediate price competition" at the moment generics enter. And there’s some truth to that. A 2024 Health Affairs study found pharmacies paid 13-18% less for generics when an authorized generic was available.But that’s not the whole story. The price drop is real-but it’s not the drop you’d expect from true competition. It’s a controlled drop. A staged drop. The authorized generic doesn’t drive prices down to the level of independent generics. It just keeps them from falling too far, too fast.

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often support authorized generics because they give them more pricing options to negotiate with. A 2023 survey found 68% of PBM executives prefer formularies that include them. But that’s not about patient savings-it’s about leverage in contracts with drugmakers.

The real losers? Independent generic manufacturers. They’re the ones who take the legal risks, invest the money, and then get undercut by the very company they’re trying to compete with. And patients? They lose too. Because fewer patent challenges mean fewer generics overall. And fewer generics mean higher prices over the long term.

Is This Legal? And Is It Changing?

Yes, it’s legal-for now. The Hatch-Waxman Act never said you couldn’t launch an authorized generic during the 180-day window. Courts have consistently upheld that. But Congress has tried to fix it. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act has been introduced multiple times, most recently in March 2023. It would ban agreements that delay authorized generic entry.And the market is changing. In 2010, 42% of generic drug markets saw an authorized generic launch. By 2022, that number had dropped to 28%. Why? Because companies are learning. They know regulators are watching. They know the FTC is ready to sue. So they’re either delaying launches, avoiding settlements, or finding new ways to extend their market control-like tweaking formulations or filing new patents on minor changes.

But here’s the bottom line: the system was designed to reward competition. Instead, it’s become a tool for delaying it. The authorized generic isn’t a solution to high drug prices. It’s a sophisticated way to keep them high while pretending you’re helping.

What’s Next?

The FTC is pushing harder. Congress is still debating. And generic companies are getting smarter. Some are now refusing to settle unless the brand commits to not launching an authorized generic. Others are filing lawsuits against companies that use them as a weapon.One thing is clear: if you want real competition in the generic drug market, you need real competitors. Not copies of the brand. Not corporate siblings. Not legal loopholes dressed up as consumer benefit. You need independent companies that can enter the market without being undercut by the very company they’re trying to replace.

Until then, the promise of affordable generics after patent expiration remains just that-a promise.

Comments

so like… the pharma bros just made a *copyright* for *copying* themselves? genius. absolute genius. 🤡

India knows this game well. We make cheap pills. They make legal copies to kill us. But we still win. Slowly.

Authorized generics represent a structural arbitrage within the Hatch-Waxman framework-essentially a regulatory capture mechanism where incumbent manufacturers exploit statutory loopholes to maintain monopolistic rent extraction under the guise of competitive entry. This is not market dynamics. It’s institutionalized predation.

Oh wow. So the drug companies are like… the bully who lets you borrow your own lunch money… but charges you 20% interest? 😭

THIS IS WHY I CAN’T AFFORD MY MEDS. MY HEART IS BREAKING. 😭💔

You’re not alone. People are fighting this. Keep speaking up. Change is possible.

It is worth noting that the economic incentives embedded within the Hatch-Waxman Act were designed to foster innovation and accessibility simultaneously. However, the emergence of authorized generics as a strategic countermeasure has introduced a significant distortion in the market equilibrium, effectively subverting the intended competitive mechanism. The consequence is a misalignment between legislative intent and market reality, which requires recalibration through legislative or regulatory intervention.

It’s wild how the system was built to help people, but now it’s helping corporations hide behind legal jargon. I just want my meds to be cheap, not a corporate chess match.

i just cried reading this. i take 3 pills a day. i’ve been rationing them. no one talks about this. why does it feel like we’re all just… collateral damage?

The authorized generic is not merely a commercial tactic-it is an ontological contradiction. It is the brand’s ghost haunting the very market it claims to liberate. The pharmaceutical industry has weaponized legitimacy: by replicating the product under a different label, it manipulates consumer trust while neutralizing market disruption. This is not competition. It is epistemological sabotage.

Bro. This is why I always say: if the system rewards you for cheating better than your competitors, you’re not in a free market-you’re in a rigged casino. 🎰💸 And guess who’s holding the dice? Big Pharma. Time to burn the table.

US pharma scam again. India makes generic. US company copies. We win. They cry. Same story every time.

so like… authorized generic = brand but cheaper? wait no it’s not cheaper? why do they even call it that?? 😅

This is such a fascinating case study in how laws can be weaponized by the powerful. I’m reading more about reverse payments now-mind blown. 🤯

It is not merely unethical-it is a systemic failure of democratic accountability. The Hatch-Waxman Act was a compromise, yes, but it was predicated on the presumption of good faith. What we now witness is a deliberate, sustained, and legally sanctioned erosion of that presumption. The FTC’s investigations are a start, but they are reactive, not preventative. We require structural reform: mandatory disclosure of all authorized generic launch plans, prohibition of simultaneous market entry during exclusivity windows, and the criminalization of reverse payment settlements as per the Actavis precedent. Until then, we are not consumers-we are hostages.