After a kidney transplant, your body doesn’t know the new organ isn’t a threat. It sees it as an invader and tries to attack it. That’s where tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids come in. Together, they form the most common immunosuppression plan used worldwide - not because they’re perfect, but because they work better than anything else we’ve tried so far.

Why This Trio Is the Standard

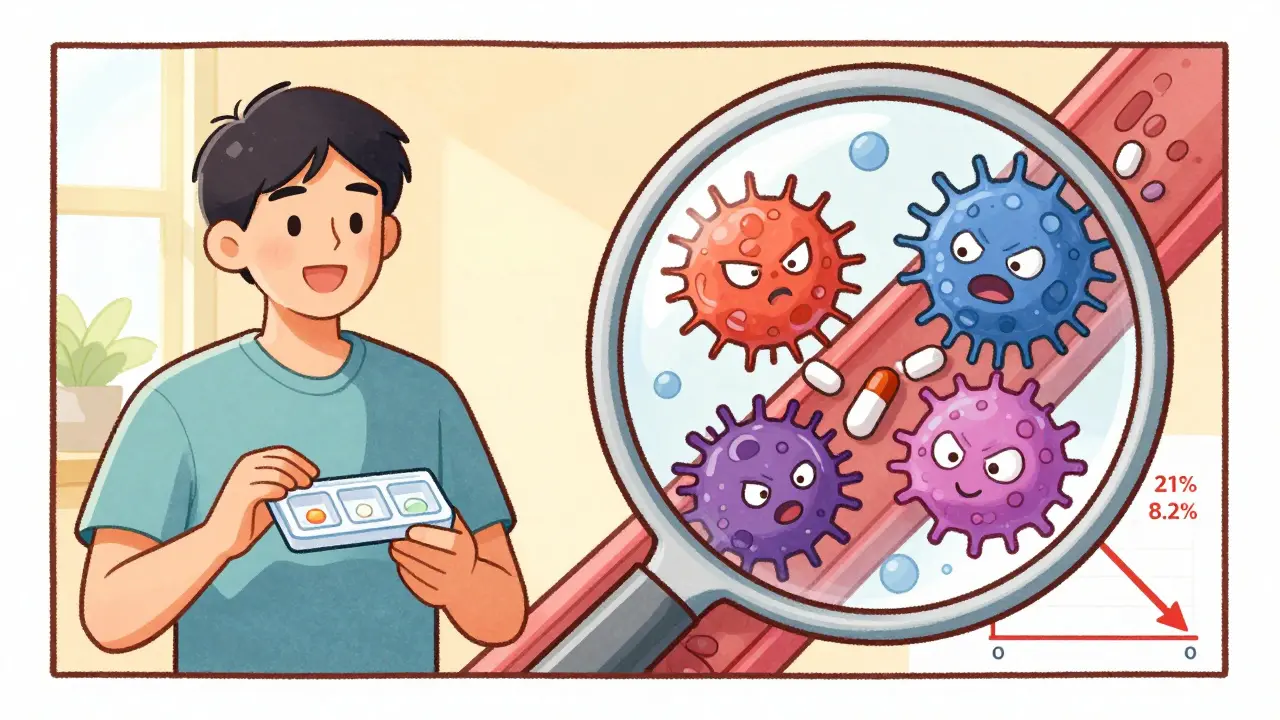

Since the mid-1990s, doctors have relied on this three-drug combo to stop acute rejection. Before this, cyclosporine was the go-to drug. But patients on cyclosporine had rejection rates around 21%. When tacrolimus and mycophenolate entered the picture, that number dropped to just 8.2%. That’s a 61% drop in rejection risk. It wasn’t a small win - it changed survival rates. This isn’t just theory. A 1998 study tracked over 200 kidney transplant patients. Those on the triple therapy had far fewer episodes of rejection confirmed by biopsy. The result? More people kept their new kidneys longer. Today, about 90% of transplant centers in the U.S. still use this approach as the starting point.How Each Drug Works

Each of these three drugs hits the immune system differently. They don’t just add up - they multiply their effect.Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor. It stops T-cells - the immune system’s main attack force - from activating. It’s taken twice a day, usually in the morning and evening. Blood levels need to be watched closely. Too low, and rejection can happen. Too high, and you risk kidney damage, tremors, or even diabetes. The target range? Between 5 and 10 ng/mL in the first year after transplant. It hits the bloodstream fast - within an hour or two - but its effects build over 12 to 24 hours.

Mycophenolate (often as mycophenolate mofetil, or MMF) blocks the production of DNA in immune cells. Without DNA, those cells can’t multiply and spread. You take it as two 500 mg or 1 g pills a day. It’s tough on the stomach. About 25 to 30% of patients get diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. Around 15% develop low white blood cell counts (leukopenia), which increases infection risk. That’s why many end up lowering the dose or stopping it altogether. It’s not the drug itself that fails - it’s the side effects.

Steroids - usually methylprednisolone or prednisone - are powerful anti-inflammatories. They’re given as a big IV dose right in the operating room, then quickly tapered down. Within a month, most patients are on 15 mg a day. By three months, it’s down to 10 mg. Steroids work fast and well, but they come with a cost: weight gain, acne, mood swings, and high blood sugar. That’s why doctors are trying to get patients off them as soon as possible.

The Trade-Offs: What You Gain and What You Lose

This combo is effective, but it’s not harmless. For every rejection you prevent, you risk something else.One in five people on this regimen develops post-transplant diabetes. That’s because tacrolimus interferes with insulin production. Suddenly, you’re managing blood sugar on top of everything else. It’s not just a nuisance - it increases heart disease risk and can damage your new kidney over time.

Then there’s the infection risk. With your immune system turned down, you’re more vulnerable. CMV (cytomegalovirus) is common. So are urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and even rare fungal infections. You’ll get regular blood tests and sometimes antiviral meds just to stay ahead of this.

And let’s not forget the long-term damage. Even if your kidney works fine for five years, chronic injury can creep in. The drugs don’t stop the slow scarring of the transplant. That’s why 25% of adults lose their graft within five years - not from rejection, but from this hidden, gradual damage.

Can You Skip the Steroids?

Many patients hate steroids. The weight gain, the moon face, the mood swings - they’re real. That’s why doctors have tested steroid-free regimens.In a 2005 study, patients got a powerful antibody called daclizumab at transplant, then stayed on just tacrolimus and mycophenolate. The rejection rate? 16.5%. Same as the group that kept steroids. And 89% of them stayed steroid-free after six months. Their quality of life improved. No more acne. No more cravings for junk food. No more feeling like you’re ballooning.

But here’s the catch: this only works if you’re low-risk. If you got your kidney from a deceased donor, or if you’ve had rejection before, skipping steroids isn’t safe. It’s not for everyone. And even then, some centers still prefer to keep a tiny dose - like 5 mg of prednisone - just in case.

Monitoring and Dosing: It’s Not Just About Pills

Taking the pills is only half the battle. The real challenge is making sure your body is getting the right amount.Tacrolimus levels vary wildly between people. Two people on the same dose can have completely different blood levels. That’s why doctors check trough levels - the lowest point in your cycle, usually right before your next dose. But newer research says that’s not enough. What matters more is the area under the curve (AUC) - how much drug your body is exposed to over 12 hours. This gives a fuller picture. Some centers now use AUC monitoring, especially for patients with unstable levels or side effects.

Mycofenolate is trickier. Its absorption drops if you take it with antacids or proton pump inhibitors (like omeprazole). That’s why you’re told to take it two hours before or after these drugs. And timing matters - some doctors separate tacrolimus and mycophenolate by 2-4 hours to reduce stomach upset.

It takes time to learn this dance. New transplant teams often spend six to twelve months getting the rhythm right. Patients need to be their own advocates - keeping a log of side effects, noting when they feel off, and reporting missed doses.

What’s Next? The Future of Transplant Drugs

The triple therapy isn’t going away anytime soon. But it’s changing.Doctors are moving toward personalized immunosuppression. Instead of giving everyone the same dose, they’re starting to look at genetics. Some people metabolize tacrolimus faster. Others are more sensitive to mycophenolate. Blood tests can now predict how you’ll respond - and adjust doses before problems start.

There’s also talk of using biomarkers - proteins or genes in your blood - to tell if your immune system is about to reject the kidney. If we can catch it early, maybe we can tweak just one drug instead of blasting the whole system.

By 2030, experts predict 15-20% fewer people will be on the full triple regimen. Steroid-free plans will grow. New drugs like belatacept (which works differently and doesn’t harm the kidney) are already being used in select cases. But for now, tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and steroids remain the backbone.

Living With This Regimen

This isn’t a cure. It’s a lifelong balance. You’re not just taking pills - you’re managing a fragile peace between your body and your new kidney.Some people do great. They stick to their schedule, get their blood drawn, and live full lives - working, traveling, raising kids. Others struggle with the side effects. One patient I spoke with said she stopped mycophenolate after three months because the diarrhea was worse than dialysis. Another said the steroids made him feel like a stranger in his own skin.

The key? Communication. Tell your team if you’re having trouble. Don’t stop a drug because you’re scared. Don’t skip a blood test because you’re busy. Your kidney isn’t just a gift - it’s a responsibility. And this regimen, flawed as it is, is still the best tool we have to protect it.

Can I stop taking my immunosuppressants if I feel fine?

No. Stopping these drugs - even if you feel great - almost always leads to acute rejection. The immune system doesn’t ‘remember’ the transplant is supposed to be safe. It will attack. Rejection can happen within days. Many patients who stop meds end up back on dialysis or needing another transplant. Never stop without your transplant team’s guidance.

Why do I need blood tests so often?

These drugs have narrow windows. Too little, and your kidney gets rejected. Too much, and you risk kidney damage, diabetes, or infections. Blood tests check your drug levels and organ function. Early on, you might need tests twice a week. After a year, it drops to monthly or quarterly. Skipping them is risky - you won’t feel the problem until it’s serious.

Does mycophenolate cause infertility?

No, mycophenolate doesn’t cause infertility. But it can harm a developing fetus. Both men and women must use birth control while taking it and for six weeks after stopping. If you’re planning pregnancy, talk to your doctor - you’ll need to switch to a safer drug like azathioprine before conceiving.

Can I drink alcohol while on this regimen?

Small amounts - like one drink a day - are usually okay. But alcohol stresses your liver, and so do these drugs. Heavy drinking increases the risk of liver damage and can interfere with how your body processes tacrolimus. If you’re diabetic or have high blood pressure, alcohol makes those worse. Best to keep it minimal and always check with your team.

What should I do if I miss a dose?

If you miss one dose, take it as soon as you remember - unless it’s close to your next dose. Never double up. If you miss two or more doses in a row, call your transplant center immediately. Missing doses raises your rejection risk. Keep a pill organizer and set phone reminders. Many patients use apps designed for transplant meds.

What to Watch For: Red Flags

You don’t need to be a doctor to spot trouble. Here’s what to watch:- Fever over 38°C without a cold or flu

- Dark urine or swelling in legs - signs of kidney trouble

- Severe diarrhea lasting more than two days

- Unexplained bruising or bleeding - could mean low platelets

- Sudden weight gain, puffiness, or increased thirst - possible diabetes

- Confusion, shaking, or vision changes - possible tacrolimus toxicity

If any of these happen, don’t wait. Call your transplant team. Early action saves kidneys.

Comments

man i just got my kidney transplant last year and this post nailed it. tacrolimus levels are a nightmare-i swear my doc checks them more than my ex checks my phone. and mycophenolate? damn, i thought i had a weak stomach till i started this shit. diarrhea so bad i started carrying extra pants in my bag. but hey, at least i’m not on dialysis anymore. 🤝

AMERICA STILL GOT THE BEST TRANSPLANT PROTOCOLS 🇺🇸🔥 nobody else even tries to match this level of science. if you're not on this triple combo, you're basically playing russian roulette with your new kidney. steroids? yeah they make you look like a moon bear but at least you're alive. #USAHEALTHCAREWINS

so let me get this straight-we’re giving people three drugs that each cause their own unique hell, just so they don’t die? brilliant. absolute masterpiece of medical compromise. it’s like giving someone a chainsaw to fix a leaky faucet. at least we’re honest about it being a dumpster fire with a 90% success rate. 🤷♂️

people don’t realize how irresponsible it is to even consider skipping steroids. this isn’t a lifestyle choice-it’s a medical necessity. if you’re too lazy to deal with acne and weight gain, you’re not ready for a transplant. your kidney deserves better than your laziness.

they don’t want you to know this, but tacrolimus was developed by a shadowy pharma consortium to keep transplant patients dependent. the ‘blood levels’ they monitor? total scam. it’s all about profit. they don’t care if you get diabetes or tremors-just as long as you keep buying the pills. and why do they say ‘steroid-free’ is risky? because they don’t have a patent on the alternative yet. 🤫

what strikes me most isn't the science-it's the humanity. this regimen isn't just about chemistry. it's about discipline, patience, and the quiet courage of showing up every day to take pills that make you feel like a ghost in your own body. we call it 'immunosuppression' but really, it's a daily surrender to a fragile peace. the body doesn't forget betrayal. and neither do we. but somehow, we keep going. not because we're brave. because we have no other choice.

mycophenolate made me so nauseous i started eating pickles at 3am like some kind of post-transplant vampire. and don’t get me started on steroids-i looked like a balloon animal that got too much helium. but here’s the kicker: i went from dialysis to hiking in the Rockies. so yeah, i’ll take the moon face if it means i can watch my kid play soccer without wheezing. this ain’t pretty-but it’s fucking beautiful.

just wanted to say-this post made me cry. not because it’s sad, but because it’s real. i’ve been on this combo for 7 years. missed doses, panic attacks over blood tests, weird rashes, the whole deal. but i’m alive. i’m coaching little league. i’m watching sunsets. this ain’t perfect, but it’s mine. thank you for writing this. you made me feel seen.

It is imperative to underscore that non-compliance with immunosuppressive regimens constitutes a statistically significant risk factor for graft loss. The data is unequivocal. While side effects are indeed burdensome, the alternative-return to dialysis or retransplantation-is both clinically and economically untenable. Adherence is not optional; it is the cornerstone of post-transplant longevity. I urge all recipients to prioritize this with the gravity it deserves.