Absolute vs. Relative Risk Calculator

Absolute Risk Reduction

How much the risk is actually reduced

Relative Risk Reduction

How much the risk is reduced compared to baseline

Number Needed to Treat (NNT)

How many people need to take the drug to prevent one event

Understanding Your Results

A smaller NNT means the treatment is more effective. For example:

- NNT = 10 means 1 out of every 10 people benefits

- NNT = 100 means 1 out of every 100 people benefits

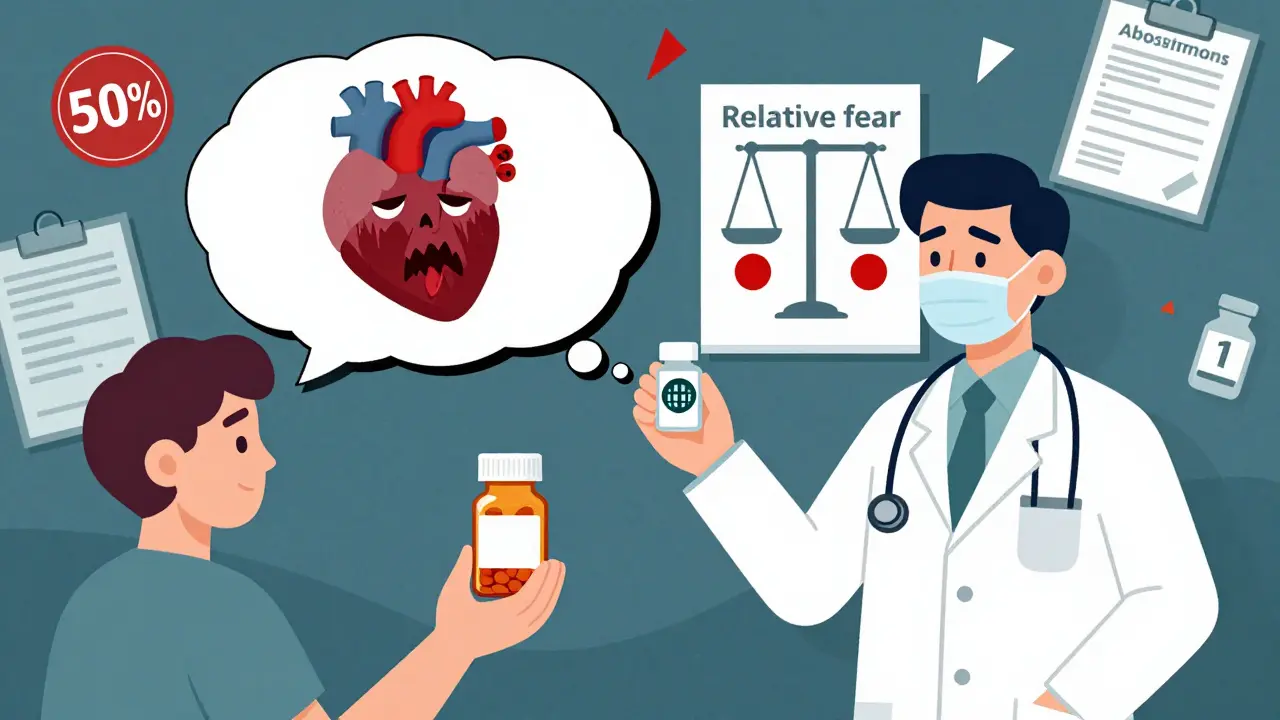

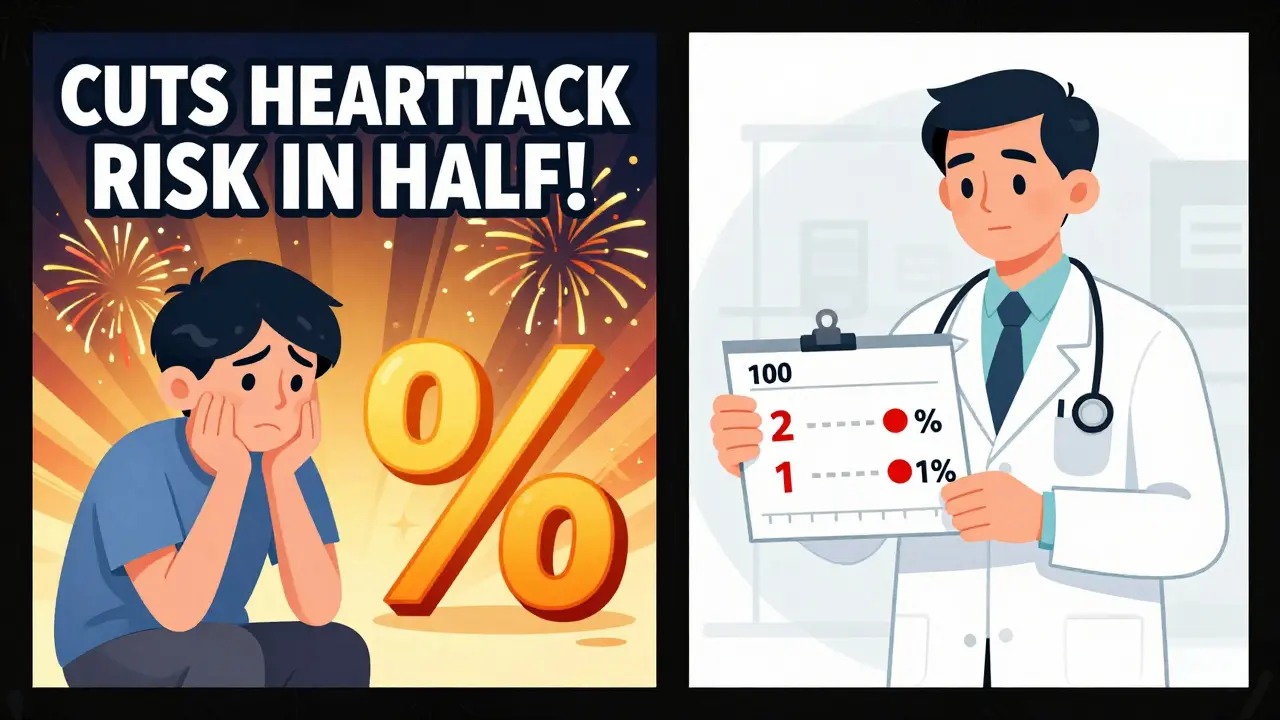

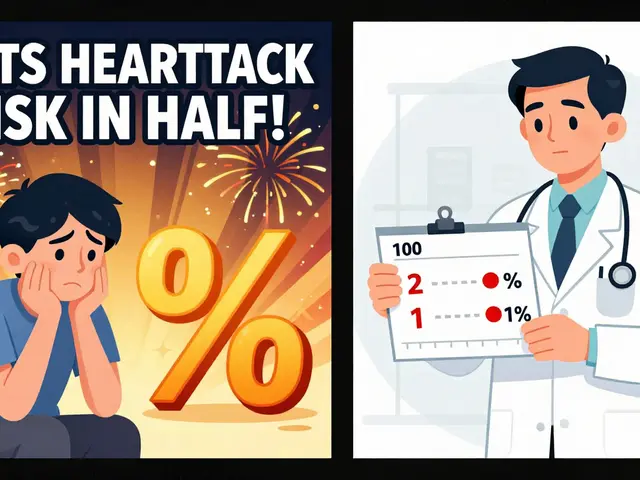

When a drug ad says it "cuts your risk of heart attack in half," you might think you’re avoiding a 50% chance of having one. But what if your real risk was only 2% to begin with? Cutting that in half means you’re now at 1% - not a dramatic change, but it sounds huge when you hear "50% reduction." This is the gap between absolute risk and relative risk, and it’s one of the most common tricks used in drug marketing - and one of the most dangerous misunderstandings in medicine.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk is the actual chance of something happening to you. It’s simple: out of 100 people like you, how many will experience this side effect or benefit? If 1 in 1,000 people on a certain drug get a rare liver problem, that’s an absolute risk of 0.1%. If 10 in 100 people get headaches, that’s 10%. These numbers don’t change based on comparisons. They’re your real-world odds.Doctors use absolute risk to decide if a treatment’s benefit is worth the cost - physical, financial, or emotional. For example, if a statin reduces your chance of a heart attack from 4% to 3% over 10 years, that’s a 1 percentage point drop. That’s the absolute risk reduction. It doesn’t sound exciting. But it’s honest. It tells you exactly what to expect.

How Relative Risk Makes Small Changes Look Big

Relative risk compares two groups: people taking the drug versus those who aren’t. It’s a ratio. If your risk goes from 2% to 1%, the relative risk reduction is 50%. That’s because 1% is half of 2%. But here’s the catch: it says nothing about the starting point. A 50% reduction sounds powerful - until you realize the original risk was tiny.Take a drug that lowers the risk of a rare cancer from 1 in 100,000 to 1 in 1,000,000. The relative risk reduction? 90%. Sounds amazing. But the absolute risk reduction? Just 0.099%. That’s less than one in a thousand. For most people, the chance was already so low that the drug barely moves the needle. Yet ads will scream "90% reduction!" because that number grabs attention.

Pharmaceutical companies know this. A 2021 study found that 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. highlight relative risk reduction - and only 12% mention the absolute numbers. Why? Because 90% sounds better than 0.099%. And when you’re selling a pill, bigger numbers sell more.

Why Both Numbers Matter - And Why One Alone Is Misleading

You can’t understand a drug’s real impact by looking at just one number. Absolute risk tells you how likely something is to happen to you. Relative risk tells you how much the drug changes that likelihood compared to not taking it. You need both.Consider venlafaxine, an antidepressant. Studies show 20% of people on it experience sexual side effects. On placebo, it’s 8.3%. The relative risk? 2.41 - meaning you’re more than twice as likely to have this side effect. That sounds alarming. But the absolute increase? Just 11.7 percentage points. So for every 100 people taking the drug, about 12 more will have this issue than if they didn’t. That’s useful context. Without it, you might assume nearly everyone on the drug will be affected.

Or think about the 2013 Fukushima nuclear disaster. News reports said cancer risk had "increased by 70%" after exposure. That’s a relative risk. But the actual baseline risk was 0.75%. After exposure, it rose to 1.25%. The absolute increase? Just 0.5 percentage points. For most people, the change was negligible - but the headline made it sound like a public health crisis.

How This Confuses Patients - And Even Doctors

Patients aren’t the only ones confused. A 2019 study found that 60% of surveyed physicians couldn’t correctly convert a relative risk reduction into an absolute one. That’s terrifying. If the people prescribing drugs don’t fully grasp the numbers, how can patients be expected to?On Reddit, a primary care doctor shared that patients regularly refuse statins because they heard it "cuts heart attack risk in half." They think that means half of all people on the drug won’t have heart attacks. In reality, it usually means their personal risk dropped from 2% to 1%. That’s not nothing - but it’s not a miracle either. The patient’s fear isn’t irrational. It’s the result of bad communication.

Another patient on a health forum wrote: "I thought a 50% reduction in heart attacks meant half the people taking the drug wouldn’t get them. I was shocked to find out it meant my risk went from 2% to 1%." That’s the gap. And it’s not just about misunderstanding - it’s about being misled.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

You don’t need to be a statistician to make smart decisions. Just ask these three questions:- What’s my chance of this problem happening if I don’t take the drug?

- What’s my chance if I do take it?

- How many people need to take this drug for one person to benefit (or avoid harm)?

The first two give you absolute risk. The third is called the Number Needed to Treat (NNT). It’s calculated by dividing 1 by the absolute risk reduction. For example, if a drug reduces your heart attack risk from 4% to 3%, the absolute reduction is 1% (0.01). So NNT = 1 ÷ 0.01 = 100. That means 100 people need to take the drug for one person to avoid a heart attack. That’s a lot of people taking a pill - and potentially experiencing side effects - for one benefit.

For side effects, there’s also the Number Needed to Harm (NNH). If 1 in 50 people on a drug gets a serious rash, the NNH is 50. That’s one person out of every 50 who takes it. You can weigh that against the NNT. Is one benefit worth one side effect in every 50 people? That’s your call.

How to Spot Manipulation in Drug Ads

Pharmaceutical ads are designed to sell. Here’s how to see through the noise:- If they say "reduces risk by X%" without mentioning the starting point, ask for the baseline.

- If they use phrases like "cut your risk in half" or "reduces risk by 70%" - check if they ever say what the original risk was.

- Look for the word "relative." If it’s not there, they’re probably hiding the absolute numbers.

- Watch for time frames. "Reduces heart attack risk by 50%" - over 5 years? 10 years? A decade-long benefit is very different from a 6-month one.

One common trick: advertising relative risk reduction for benefits while using absolute risk for side effects. For example: "Reduces stroke risk by 40%" (relative) but "only 2% of users experience nausea" (absolute). That’s a setup. The benefit sounds huge. The side effect sounds small. But if the stroke risk was only 2% to begin with, the absolute benefit is 0.8%. And 2% nausea means 1 in 50 people feel sick - which isn’t minor for someone who doesn’t need the drug.

What’s Changing - And What’s Still Broken

Regulators are starting to catch on. In 2023, the FDA released draft guidelines requiring clearer presentation of both absolute and relative risks in direct-to-consumer ads. The European Medicines Agency already requires both in patient leaflets. But enforcement is weak in the U.S., and many ads still slip through.Medical schools are finally teaching this. Harvard introduced a required course on interpreting medical statistics in 2022 after finding that 68% of graduating students couldn’t explain the difference between relative and absolute risk. That’s a start. But most patients still get their info from ads, YouTube videos, or Google searches - not medical school lectures.

Visual tools help. A pictogram showing 100 people - coloring in 2 red dots for heart attack risk, then 1 after the drug - makes the difference instantly clear. A 2016 Cochrane Review found these simple images improve understanding far more than numbers alone. Yet most doctors still rely on verbal explanations.

Bottom Line: Know the Numbers Before You Decide

Drugs aren’t magic. They have trade-offs. A 90% relative risk reduction sounds like a miracle. But if your absolute risk was 0.01%, the drug barely changes your life. On the other hand, a 10% absolute risk reduction for a common condition like high blood pressure could mean avoiding a stroke - and that’s huge.Your health decisions shouldn’t be based on marketing slogans. They should be based on your actual risk, your values, and the real numbers. Always ask for absolute risk. Always ask for the baseline. Always ask how many people need to be treated for one to benefit.

When you understand both absolute and relative risk, you stop being a passive recipient of drug ads. You become an informed partner in your care. And that’s the only kind of decision that truly matters.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk is your actual chance of something happening - like having a heart attack or a side effect. It’s expressed as a percentage or rate, such as 2 in 100. Relative risk compares your risk on a drug to your risk without it. It’s a ratio - like "cutting your risk in half." Relative risk sounds bigger, but it doesn’t tell you your real risk - only how much it changed.

Why do drug ads use relative risk instead of absolute risk?

Because relative risk numbers are bigger and more attention-grabbing. A 50% reduction sounds impressive. A 1% absolute reduction doesn’t. Drug companies know this. Studies show 78% of U.S. drug ads highlight relative risk reduction - and only a small fraction mention the actual baseline risk. It’s not illegal - just misleading.

How do I know if a drug’s benefit is worth the risk?

Ask for two numbers: your absolute risk without the drug, and your absolute risk with it. Then calculate the absolute risk reduction (the difference). If the benefit is small - like a 1% reduction - ask how many people need to take the drug for one person to benefit (the NNT). If the NNT is high (like 50 or 100), the benefit is narrow. Also ask about side effects and the Number Needed to Harm (NNH). Compare the two.

Can relative risk ever be useful?

Yes - but only when you know the absolute risk too. Relative risk helps researchers compare how a drug works across different populations. For example, if a drug reduces heart attack risk by 30% in people with high cholesterol and 20% in healthy people, that tells you it works better in higher-risk groups. But for you as a patient, absolute risk tells you whether it matters in your life.

What should I do if my doctor only gives me relative risk numbers?

Ask for the absolute numbers. Say: "Can you tell me what my chance of having this problem is without the drug? And what’s my chance with it?" If they can’t answer, ask for the patient information leaflet - it should have both. If they push back, consider getting a second opinion. You have the right to understand the real numbers behind your treatment.

Comments

Bro, I just had my doc hand me a statin script and say "cuts heart attack risk in half!" I thought I was getting a superhero pill. Turns out my risk was 2% → 1%. I almost threw it in the trash. Now I get why people don’t trust medicine.

omg yes!!! i’ve been trying to tell my mom this for years she thinks if a drug says "50% reduction" it means she’ll never get sick 😭 i showed her your post and she finally gets it. thank you for writing this 💖

It’s not merely misleading-it’s epistemologically dishonest. The pharmaceutical industry weaponizes cognitive biases through statistical obfuscation, leveraging the Dunning-Kruger effect in lay audiences who lack the mathematical literacy to parse relative from absolute risk. This isn’t marketing-it’s structural manipulation under the guise of informed consent.

Okay but let’s be real-this whole thing is just a distraction. The real issue isn’t that drug ads use relative risk-it’s that the entire medical-industrial complex is built on selling fear and pills. You think they care if you understand 0.099% vs 90%? No. They care if you’re anxious enough to swallow something daily. The numbers are just the glitter on the snake oil. They don’t want you informed-they want you dependent. And don’t even get me started on how doctors are trained to parrot this nonsense without ever calculating NNTs themselves. It’s all theater. The patient? Just the audience.

i just read this while waiting for my blood pressure check. my dr gave me the "50% reduction" line last week. i didn’t say anything. now i know what to ask next time. thank you.

This is one of the most important posts I’ve read in years. Seriously. We’re taught to trust doctors and ads without asking the real questions. But knowledge is power-and knowing the difference between absolute and relative risk? That’s like unlocking a secret level in life. Don’t just take the pill-ask for the math. Your future self will thank you. 💪🧠

Consider the ontological dissonance inherent in risk commodification: when a corporeal vulnerability (e.g., myocardial infarction) is reduced to a probabilistic metric, and then rhetorically inflated via ratio-based framing, we witness the neoliberal subsumption of embodied experience into marketable abstraction. The 90% reduction is not a medical truth-it is a semiotic spectacle designed to induce pharmacological compliance. 🤔💊

As a pharmacist, I see this every day. Patients refuse blood pressure meds because they think "50% reduction" means they won’t have a stroke. Meanwhile, their real risk was 3% → 2%. I always show them a little grid: 100 people, 3 red dots → 2 red dots. That’s it. They get it. The problem isn’t the science-it’s the communication. We need pictograms in every ad. Simple. Human. Real.

Man, I used to work in pharma marketing. We were told: "Always lead with the relative risk. Never mention the baseline unless they ask. And if they ask, make them wait five minutes while you "look up the data."" We knew it was BS. But the bonuses were real. Sorry, folks. We sold you smoke and mirrors.

This is a controlled distraction. The real agenda: normalize chronic pharmaceutical dependency. Absolute risk data is suppressed because it reveals the inefficacy of most chronic disease medications. The FDA? Complicit. The AMA? Complicit. The system is designed to keep you medicated, not healed. The numbers are not wrong-they are weaponized.

The statistical illiteracy epidemic is a feature, not a bug. The pharmaceutical elite rely on the populace’s inability to compute conditional probabilities. The 78% statistic cited is not an anomaly-it is the operational baseline. Your ignorance is their leverage. The only defense is epistemic vigilance. Or, as I tell my patients: "If they won’t give you the denominator, don’t take the numerator."

One thing I’ve learned working in public health: the NNT is the real litmus test. If the NNT is over 50 for a drug you’re taking daily for 10+ years, you’re essentially gambling. For a 65-year-old with high cholesterol, maybe it’s worth it. For a 35-year-old with no other risk factors? Probably not. But no one ever tells you that. We need a standardized risk-benefit dashboard for every prescription-like nutrition labels. Imagine if your pill had: "NNT: 100 | NNH: 25 | Absolute benefit: 1%". That would change everything.

The presentation of medical risk in direct-to-consumer advertising constitutes a violation of the principle of informed consent, insofar as the information provided is systematically skewed toward amplification of perceived benefit while minimizing perceived risk. The absence of absolute risk figures in the majority of promotional materials renders the patient’s decision-making process not merely uninformed, but structurally compromised. Regulatory intervention is not merely advisable-it is ethically imperative.