When your liver fails, your kidneys don’t just slow down-they shut down. Not because they’re damaged, but because your body’s blood flow has gone haywire. This is hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), a deadly but often misunderstood complication of advanced liver disease. It doesn’t show up on biopsies. It doesn’t respond to dialysis alone. And if you don’t recognize it fast, you could lose weeks-maybe days-of life.

What Exactly Is Hepatorenal Syndrome?

Hepatorenal syndrome isn’t kidney disease. It’s liver disease turning on the kidneys. In people with cirrhosis, the liver can’t manage blood pressure or fluid balance anymore. Blood pools in the abdomen and gut, triggering a chain reaction: arteries widen where they shouldn’t, blood pressure drops where it matters most, and the kidneys respond by tightening their blood vessels. No injury. No scarring. Just silence. The kidneys stop filtering because they’re being starved of blood.This isn’t a slow decline. Type 1 HRS can spike creatinine from 1.5 to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. That’s a 60-70% drop in kidney filtration. Without treatment, median survival is just 2 weeks. Type 2 is slower, creeping up over months, tied to stubborn ascites that won’t go away no matter how many diuretics you take. Both are medical emergencies.

How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

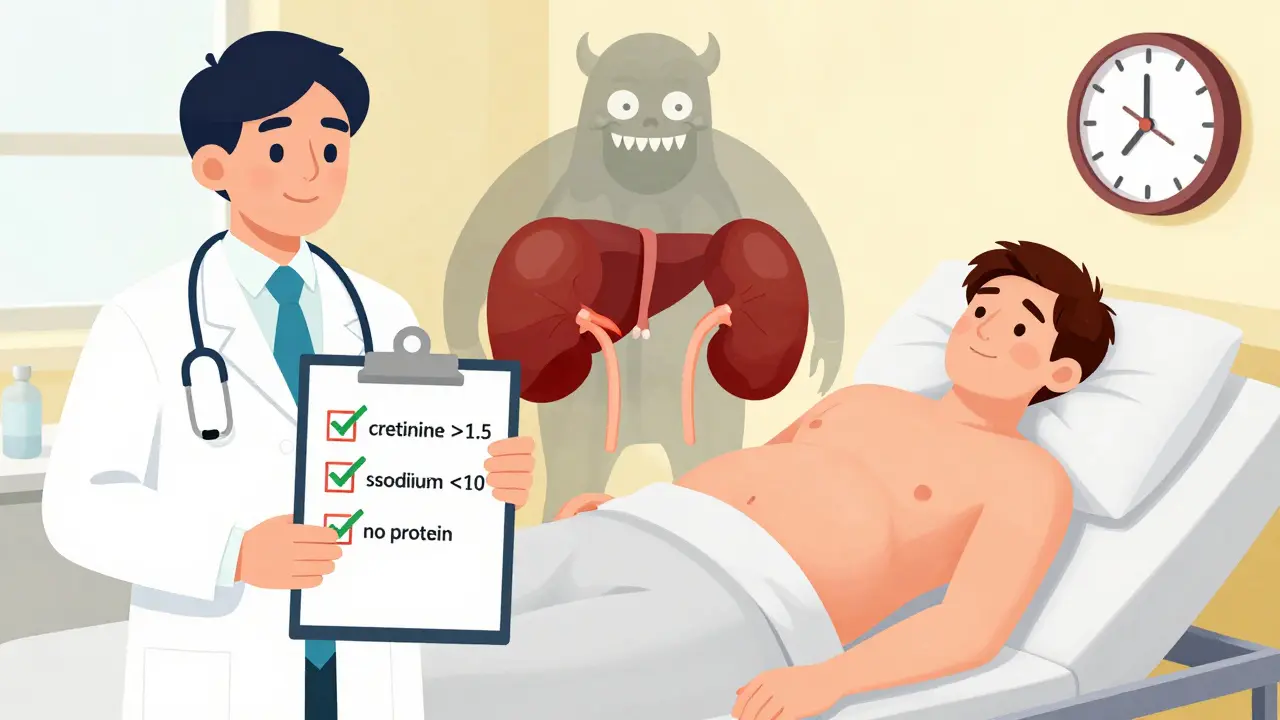

There’s no single test for HRS. Diagnosis is a process of elimination. First, your doctor rules out everything else: urinary blockages, kidney infections, drug damage, or simple dehydration. Then they check for three key signs:- Serum creatinine above 1.5 mg/dL (Type 2) or rising to 2.5 mg/dL or more (Type 1)

- Urine sodium under 10 mmol/L

- No protein in the urine and no blood in the urine

They’ll also test your fractional excretion of sodium (FeNa)-if it’s below 0.01%, that’s a red flag. And they’ll give you a test dose: stop diuretics, give you 1 gram per kilogram of albumin intravenously, and wait 48 hours. If your kidneys don’t bounce back, HRS is likely.

Here’s the catch: 25-30% of cases are misdiagnosed. Many doctors mistake it for acute tubular necrosis or just ‘bad kidney function in cirrhosis.’ That’s dangerous. Treating HRS like regular kidney failure means missing the real problem-and missing the only treatments that work.

What Triggers It?

HRS doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It’s usually the final blow after another crisis hits the liver. The most common triggers:- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP): 35% of cases. Even a mild belly infection can send HRS into overdrive.

- Upper GI bleeding: 22%. Blood in the gut pulls fluid out of circulation, crashing blood pressure.

- Acute alcoholic hepatitis: 11%. A sudden liver flare can trigger the same cascade as infection.

- Overuse of diuretics or NSAIDs: 15%. These drugs are often the last straw.

One patient story from a 2023 survey tells it plainly: ‘My dad had a small infection after a colonoscopy. Two days later, his creatinine jumped from 1.6 to 3.8. No one thought it was HRS until it was too late.’

What Are the Treatment Options?

There’s no magic pill. But there are treatments that can buy time-and sometimes save lives.Type 1 HRS: The gold standard is terlipressin + albumin. Terlipressin is a vasoconstrictor that tightens blood vessels in the gut, redirecting blood flow to the kidneys. Albumin helps hold fluid in the bloodstream. Together, they improve kidney function in about 44% of patients within two weeks. But it’s not easy. Side effects include severe abdominal pain, low blood pressure, and heart rhythm problems. One patient reported: ‘I got terlipressin and my creatinine dropped from 3.8 to 1.9 in 10 days-but I was in so much pain I had to cut the dose in half.’

In the U.S., terlipressin was FDA-approved in December 2022 under the brand name Terlivaz™. Each 1mg vial costs $1,100. A full 14-day course? Around $13,200. Many insurers still fight coverage. That’s why some hospitals still use off-label combinations like midodrine and octreotide-cheaper, but less effective.

Type 2 HRS: If you’re stuck with stubborn ascites, TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt) can help. It reroutes blood around the liver, reducing pressure. Studies show 60-70% of patients see kidney improvement. But there’s a trade-off: 30% develop hepatic encephalopathy-brain fog, confusion, even coma.

Why Liver Transplant Is the Only Real Cure

No drug fixes HRS permanently. Only a new liver does. That’s why transplant centers now list every Type 1 HRS patient immediately-even if their creatinine drops after treatment. Why? Because even if the kidneys recover, the liver is still failing. And HRS will come back.Data from UNOS shows: 71.3% of HRS patients who get a transplant survive one year. Without it? Just 18.2%. One patient wrote on a support forum: ‘We were on the transplant list with a MELD-Na of 28. We knew if we waited, we wouldn’t make it.’

Even the scoring system for transplant priority changed in 2022. MELD-Na now weighs kidney function more heavily. HRS patients get bumped up the list faster. That’s life-saving.

What’s New in Research?

Scientists aren’t waiting for transplants to be the only answer. New biomarkers are being tested to catch HRS before it hits. Urinary NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) is showing promise-levels above 0.8 ng/mL in high-risk cirrhotics may predict HRS days before creatinine rises. The PROGRESS-HRS trial is validating this now.Other drugs are in trials: PB1046 (a vasopressin agonist), alfapump® (a wearable device that drains ascites automatically), and new agents targeting inflammation and gut bacteria. Early results suggest these could reduce HRS-related deaths by 30-40% by 2027-if they get approved and become affordable.

The Real Problem: Access and Awareness

Here’s the ugly truth: HRS is treatable, but only if you’re in the right place. In North America, 63% of patients get vasoconstrictors. In sub-Saharan Africa, that number is 11%. Most community hospitals don’t have protocols. Only 35% of U.S. hospitals have a formal HRS pathway. Specialists see it often. Generalists? They miss it.Patients report delays averaging 7.2 days before diagnosis. 63% were misdiagnosed at least once. Insurance denials are common-even when guidelines are met. One caregiver said: ‘We got the diagnosis right, but the hospital said terlipressin was ‘experimental.’ We had to fight for six weeks just to get the first dose.’

Meanwhile, quality improvement studies show what works: standardized protocols. At Mayo Clinic, after implementing a clear HRS checklist, diagnosis time dropped from 5.3 days to 1.8 days. Vasoconstrictor use jumped from 54% to 89%. And 30-day survival rose by 22%.

What Should You Do If You or a Loved One Has Cirrhosis?

If you have advanced liver disease, here’s your action plan:- Know the signs: sudden swelling, less urine, confusion, fatigue that won’t quit.

- Ask your doctor: ‘Could this be HRS?’ Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- Get your creatinine and urine sodium checked regularly-especially after infection, bleeding, or a hospital stay.

- Stop NSAIDs, avoid over-diuresis, and never ignore signs of infection.

- If you’re not already on a transplant list, ask if you qualify. HRS is a strong indicator you need one.

This isn’t a condition you can manage alone. It needs a team: hepatologist, nephrologist, transplant coordinator. If your hospital doesn’t have one, ask for a referral to a liver center. Time isn’t just money here-it’s life.

Is hepatorenal syndrome the same as kidney failure?

No. Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is kidney failure caused by advanced liver disease, but the kidneys themselves aren’t damaged. In typical kidney failure, there’s physical injury-like from toxins or blockages. In HRS, the kidneys shut down because blood flow gets redirected away from them due to circulatory changes from liver failure. No scarring. No inflammation. Just functional collapse.

Can HRS be reversed without a liver transplant?

Sometimes, but only temporarily. In Type 1 HRS, terlipressin and albumin can improve kidney function in about half of patients, lowering creatinine levels and buying weeks or months. Type 2 HRS may improve with TIPS or better ascites control. But without a transplant, the liver keeps failing, and HRS almost always returns. Only a new liver offers a lasting solution.

Why is terlipressin not widely available in the U.S.?

Terlipressin was approved by the FDA in December 2022 under the brand name Terlivaz™, but it’s expensive-about $13,200 for a 14-day course. Many insurers still consider it high-cost and require prior authorization. Some hospitals still use off-label alternatives like midodrine and octreotide because they’re cheaper, even though they’re less effective. Access is better at transplant centers and academic hospitals, but many community clinics still lack it.

How do doctors tell HRS apart from other types of kidney injury?

They look for three things: 1) No structural kidney damage (no blood or protein in urine, normal ultrasound), 2) Urine sodium below 10 mmol/L, and 3) No improvement after stopping diuretics and giving albumin. Blood tests like fractional excretion of sodium (FeNa) below 0.01% are also key. If all these fit and there’s advanced liver disease, HRS is likely. If kidney damage shows up on biopsy or imaging, it’s something else.

Can HRS happen in people without cirrhosis?

Rarely. HRS is almost always tied to cirrhosis with portal hypertension. There are a few reports of it in acute liver failure (like from drug overdose or viral hepatitis), but even then, it’s linked to the same circulatory collapse seen in cirrhosis. If someone has kidney failure without cirrhosis, it’s almost certainly not HRS.

What’s the survival rate for someone with Type 1 HRS?

Without treatment, median survival is only 2 weeks. With terlipressin and albumin, about 38.7% survive one year. But if you get a liver transplant, your one-year survival jumps to 71.3%. That’s why transplant centers now list all Type 1 HRS patients immediately-even if their kidney numbers improve with treatment. The liver is still failing.

Are there any new drugs coming for HRS?

Yes. Three drugs are in late-stage trials. PB1046 targets vasopressin receptors to improve blood flow. Alfapump® is a wearable device that drains ascites automatically, helping Type 2 HRS. And researchers are testing biomarkers like urinary NGAL to catch HRS before creatinine rises. These could reduce deaths by 30-40% by 2027-if they’re approved and made accessible.

Comments

This is one of those conditions that gets buried under 'liver failure' talk. The fact that kidneys aren't damaged but just starved of blood is wild. I've seen patients on dialysis for months with HRS and it just doesn't stick because the root isn't touched. Albumin + terlipressin isn't magic but it's the closest thing we got before transplant.

Also, that 25-30% misdiagnosis rate? That's criminal. Every ER doc should have a HRS checklist stuck to their monitor.

HRS is the silent killer no one talks about 😤 I’ve been in the ICU with cirrhotic patients and the moment creatinine spikes? That’s the point of no return unless you’re FAST. Terlivaz™ is a godsend but why is it still a luxury? 🤬 We need this in every community hospital. Stop treating HRS like a kidney issue - it’s a liver emergency. #HepatorenalAwareness

They’re hiding the truth. Terlipressin was approved in 2022 but big pharma and the FDA are still pushing the expensive version because they make billions off dialysis and transplant waiting lists. The real cure? A liver transplant. But why do only 18% survive without it? Because the system doesn’t want you to get one. They profit from the slow death. 🕵️♀️

Great breakdown. I work in a rural clinic in India and we rarely see terlipressin. We rely on albumin infusions and cautious diuretic withdrawal. The urine sodium <10 mmol/L and FeNa <0.01% are our best clues. We don’t have TIPS or transplant access, but recognizing HRS early still saves weeks of suffering. Knowledge is the only medicine we have here.

Let’s be real - most of these 'HRS protocols' are just glorified guesswork. The diagnostic criteria are a mess. Urine sodium? FeNa? Albumin challenge? All retrospective. No imaging, no biopsy, no definitive marker. It’s a diagnosis of exclusion built on shaky stats. And now we’re spending $13k on a drug with 44% response rate? This is medicine playing roulette.

To anyone reading this: if you or someone you love has cirrhosis, don’t wait. Don’t assume the doctor will catch it. Ask for creatinine and urine sodium. Write it down. Bring it up at every visit. HRS doesn’t knock - it breaks down the door. I watched my mom go from 'just tired' to ICU in 72 hours. You have to be the advocate. You are their voice. 🫂

HRS is not kidney failure. Its liver failure pretending to be kidney failure. Simple. No need to overcomplicate. Albumin + terlipressin works. Transplant is the only fix. Stop wasting time on dialysis. And yes, if you have ascites and your pee is clear but you're not peeing much? That's the sign. Go now.

We treat organs like they’re separate machines. But the body isn’t a car with interchangeable parts. The liver doesn’t just 'fail' - it unravels the entire circulatory contract. HRS is the body’s final betrayal. The kidneys don’t quit - they’re forced to. We’re not curing disease. We’re negotiating with collapse. And the only real solution? A new organ. A new beginning. A new soul. But we’re still stuck in the machine age.

This is the kind of post that gives me hope. We’re finally talking about HRS like it’s real. Not just a lab value. Not just 'end-stage'. It’s a biological emergency with a window. And if we push for protocols, education, and access - we can beat this. I’ve seen it happen. It’s not magic. It’s persistence.

So let me get this straight - we have a $13k drug that works half the time, and the only real cure is a transplant that 80% of people can’t access? And we call this healthcare? 🤡 The real HRS isn’t in the liver or kidneys. It’s in the system. We’re diagnosing the disease but ignoring the infrastructure. Funny how the people who need this most are the ones who can’t even get a referral.

I work as a transplant coordinator. Every Type 1 HRS patient we see gets listed immediately. No exceptions. We’ve seen creatinine drop from 4.2 to 1.8 with terlipressin - and then climb back to 3.9 three weeks later because the liver kept failing. The kidneys are a mirror. They reflect what’s broken upstream. If you treat the kidney, you’re treating the reflection. We treat the liver. Or we don’t treat at all.