Most people think of a medication overdose as a one-time emergency - a 911 call, a dose of naloxone, a hospital stay, and then, hopefully, recovery. But for many survivors, the real battle begins after they leave the ER. The body doesn’t just bounce back. Some damage is permanent. And it’s not just about the drug you took - it’s about how long your brain went without oxygen, how your organs reacted, and whether anyone ever checked on you again.

Brain Damage Isn’t Always Obvious

When you overdose on opioids, benzodiazepines, or even too much sleep aid, your breathing slows or stops. Your heart keeps beating, but your brain is starving. After just four minutes without oxygen, brain cells start dying. That’s faster than most people can call for help - especially if they’re alone. Survivors often walk away thinking they’re fine. But the damage hides in plain sight. Sixty-three percent of overdose survivors report lasting memory problems. That’s not forgetting where you put your keys. That’s forgetting what you had for breakfast, or the name of your own child’s teacher. Fifty-seven percent struggle with concentration. Simple tasks like paying bills or following a recipe become overwhelming. Thirty-one percent say they can’t make decisions anymore. One Reddit user, after an oxycodone overdose, wrote: “Two years later, I still can’t remember conversations from 10 minutes ago.” This isn’t just “brain fog.” It’s hypoxic brain injury - the same kind seen after cardiac arrest. The longer the oxygen loss, the worse the damage. People who went without oxygen for more than 10 minutes were over three times more likely to have permanent cognitive decline than those who got help within five minutes. And it’s not just memory. Forty-two percent have trouble with balance. Thirty-eight percent lose fine motor control - buttons, writing, holding a cup become hard. Twenty-nine percent struggle to speak clearly. Twenty-three percent report hearing issues. These aren’t rare side effects. They’re the new normal for nearly two out of three survivors.Organs Don’t Heal the Same Way

Your brain isn’t the only organ that pays the price. Overdose triggers a chain reaction across your body. Opioid overdoses cause respiratory depression. That means your lungs stop working well enough to oxygenate your blood. The result? Your kidneys get damaged. Twenty-two percent of non-fatal overdose survivors develop kidney problems. Your heart gets stressed - 18% face long-term heart rhythm issues or high blood pressure. Fluid builds up in the lungs. Pneumonia from inhaling vomit happens in six percent of cases. And eight percent suffer strokes, even if they’re young and otherwise healthy. Benzodiazepines - like Xanax or Valium - don’t just knock you out. They depress your central nervous system for hours. Twenty-seven percent of survivors still have memory loss and trouble making decisions six months later. It’s not just tiredness. It’s your brain’s wiring that’s changed. Stimulant overdoses - from Adderall, Ritalin, or even too much caffeine pills - are different. They don’t slow you down. They push you past your limits. Thirty-one percent of survivors end up with chronic high blood pressure or irregular heartbeats. Nineteen percent develop anxiety so severe it turns into full-blown psychosis. One woman in Manchester told her doctor: “I used to take Adderall to stay awake for work. Now I can’t sleep, and I hear voices when I’m alone.” And then there’s paracetamol (acetaminophen). People think it’s safe. It’s in every medicine cabinet. But take too much - even just 15 pills - and your liver starts dying. The problem? You feel fine for 48 to 72 hours. By the time you’re vomiting and jaundiced, it’s too late. Forty-five percent of those who don’t get treatment within eight hours develop cirrhosis or chronic liver failure. No second chances.The Invisible Wounds: Mental Health After Surviving

Surviving an overdose isn’t a victory. It’s a trauma. And your mind doesn’t recover the way your body might. Seventy-three percent of survivors develop a diagnosable mental health condition afterward. Forty-one percent get PTSD. Thirty-eight percent fall into major depression. Thirty-three percent battle constant, overwhelming anxiety. These aren’t temporary reactions. In 58 percent of cases, they last over a year. Why? Because nearly dying changes you. You remember the panic. The helplessness. The sound of your own breath stopping. You wake up wondering if you’ll ever feel normal again. And too often, no one asks. Only 28 percent of overdose survivors get mental health follow-up within 30 days. The rest are discharged with a pamphlet and told to “stay clean.” But what does that mean when your brain is damaged? When you can’t remember why you took the pills in the first place? When you’re terrified of being alone? One man on a UK recovery forum wrote: “I was lucky to be alive. But every day feels like walking through fog. My doctors say I’m fine. But I’m not. I can’t work. I can’t hold a conversation. I don’t know who I am anymore.”

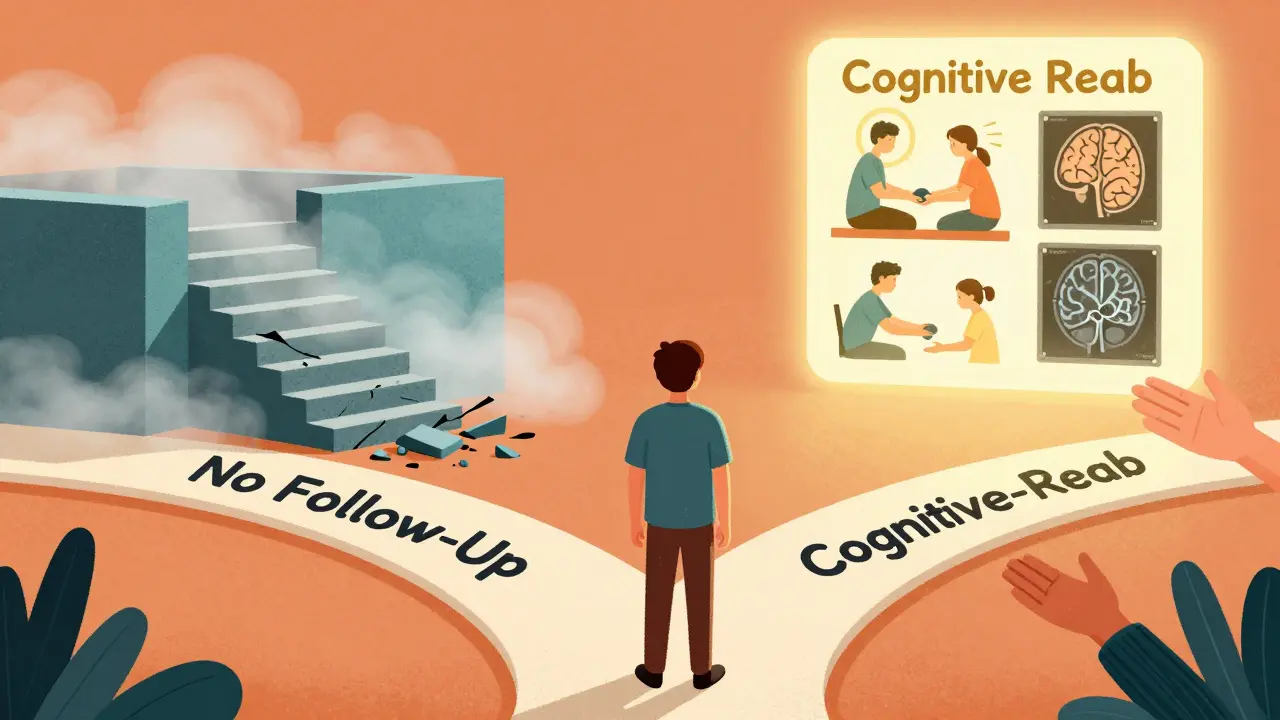

The System Fails Survivors

Here’s the cruel part: the system that’s supposed to help you after an overdose often doesn’t. In the U.S., 41 percent of overdose survivors are discharged without any referral to follow-up care - not for brain injury, not for liver damage, not for depression. Emergency rooms treat the acute event and move on. They don’t track the long-term toll. Even when they do, the tools aren’t there. Only 47 percent of emergency departments document what kind of monitoring a survivor needs. Only 19 percent of hospitals have formal protocols for long-term care after overdose. And in rural areas, it’s worse. The average time to give naloxone? Over 11 minutes. That’s 6 minutes too late to prevent brain damage. And then there’s the cost. The average lifetime healthcare cost for a survivor with permanent brain injury? Over $1.2 million. For someone who recovers fully? Less than $300,000. But insurance doesn’t cover “long-term neurological rehab” unless you’re a stroke patient. Overdose survivors? They’re often treated like addicts, not patients.What Can Be Done?

Change is starting - slowly. In 2023, the U.S. government allocated $156 million to study brain injury from overdoses. The American Medical Association now requires doctors to run neurological tests within 72 hours of overdose survival. That’s a start. But real change means three things:- Screening. Every survivor needs a brain scan, liver function test, heart monitor, and mental health evaluation - not just a quick check-in.

- Referrals. Hospitals must connect survivors to neurologists, addiction counselors, and occupational therapists - not just hand them a phone number.

- Education. The public needs to know the signs: unresponsiveness, slow breathing, pinpoint pupils. And they need to know that naloxone saves lives - and that it’s not a license to wait.

You’re Not Alone - But You Might Feel Like It

If you’ve survived an overdose, you’re not broken. You’re injured. And like any injury, healing takes time, support, and the right care. You might forget things. You might feel anxious for no reason. You might not be able to work like you used to. That’s not weakness. That’s biology. The first step? Ask for help - even if no one asked you first. Talk to your doctor about brain injury. Request a liver panel. Ask for a mental health referral. If they say no, ask again. Or go to a different clinic. Your life after overdose doesn’t have to be defined by what happened. But it will be shaped by what you do next. And you deserve more than a pamphlet. You deserve real care.Can you recover from brain damage caused by a medication overdose?

Some recovery is possible, especially if treatment starts quickly. The brain can rewire itself over time through therapy, cognitive training, and physical rehabilitation. But if oxygen deprivation lasted more than 10 minutes, permanent damage is likely. Memory loss, balance issues, and trouble thinking may never fully go away - but they can improve with consistent support.

How long after an overdose do long-term effects appear?

Some effects show up right away - confusion, dizziness, weakness. Others take months. Liver damage from paracetamol can take 48-72 hours to become visible. Cognitive decline and mental health issues often emerge 3-6 months later. That’s why follow-up care is critical - symptoms can be delayed, but the damage isn’t.

Is it possible to die from a non-fatal overdose later on?

Yes. Survivors of non-fatal overdoses have a much higher risk of dying in the next year - not from another overdose, but from complications like liver failure, heart disease, or suicide. The trauma of nearly dying, combined with chronic health damage, creates a dangerous cycle. That’s why long-term monitoring isn’t optional - it’s life-saving.

Can paracetamol overdose cause permanent liver damage even if I didn’t feel sick?

Absolutely. Paracetamol overdose is silent. You might feel fine for two days. By the time nausea, yellow skin, or abdominal pain appear, your liver is already failing. Forty-five percent of those who don’t get treatment within eight hours develop chronic liver disease - even if they never had liver problems before.

Why don’t hospitals do more to help overdose survivors after they leave?

Many hospitals treat overdose as an acute event - not a chronic condition. There’s no funding, no protocol, and little training. Staff are overwhelmed. Insurance doesn’t cover long-term neurological rehab for overdose survivors. And stigma plays a role - too many still see it as a “choice” rather than a medical crisis. Change is happening, but it’s slow.

What to Do Next

If you or someone you know survived an overdose:- Ask for a brain scan (MRI or CT) and cognitive testing.

- Request blood tests for liver and kidney function - even if you feel okay.

- See a mental health professional, even if you think you’re “fine.”

- Find a support group. You’re not alone - and isolation makes recovery harder.

- Keep a journal. Track memory lapses, mood changes, or physical symptoms. That info helps doctors.

Comments

So let me get this straight - you take a few pills, wake up in the hospital, and suddenly you’re supposed to be fine? Bro. My cousin did that with Xanax and now she can’t remember her own wedding. No one even asked if she was okay after they discharged her. Just a pamphlet and a pat on the back. Like she chose this. Like it was a bad decision and not a broken system.

It’s not about recovery. It’s about recognition. The body repairs tissue, but the mind doesn’t have a reset button. When your brain loses oxygen, it’s not a glitch - it’s a rewrite. And society treats survivors like they’re broken software instead of damaged humans. We don’t have language for this kind of injury. We only have judgment.

Y’ALL. I just read this and I’m crying. Not because it’s sad - because it’s TRUE. My sister overdosed on acetaminophen and they sent her home with a ‘take it easy’ note. Three months later she couldn’t tie her shoes. Her hands shook. She forgot how to say ‘coffee.’ No one told her she might never get back to normal. We need to stop pretending this is just ‘addiction.’ It’s a medical emergency with lifelong consequences. We need scans. We need rehab. We need to stop acting like it’s their fault. 🥺💔

paracetamol is a silent killer. i knew a guy who took 12 pills ‘cause he was stressed. felt fine for 2 days. then he started pukin blood. liver gone. transplant came too late. doc said if he’d come in at 8 hrs he’da been fine. but no one knows that. even drs forget. u gotta tell em. scream it. paracetamol = slow suicide if u overdose. 🤯

You are NOT broken. You are wounded. And wounds heal - but only if someone holds your hand while they do. If you’re reading this and you’re surviving - I see you. I believe you. Go ask for that brain scan. Demand the mental health referral. Write down what you forget. Keep going. You’re not alone. And your life still matters. 💪❤️

This is what happens when you treat addiction like a disease instead of a moral failure. People take risks, they pay consequences. If you can’t handle the pressure of life, maybe don’t medicate yourself into oblivion. Hospitals shouldn’t be giving out free MRIs to people who made bad choices. Accountability matters. This article reads like a victim card factory.

the fact that we treat overdose survivors like they’re disposable… 😔 it breaks me. i had a friend who survived an oxycodone overdose. they did the rehab. the therapy. the journaling. and still - no one asked if she could remember her mom’s voice. no one tested her for brain damage. she just got told to ‘stay strong.’ i wish someone had told her to get an MRI. she’s 27. she shouldn’t be forgetting how to spell her own name. 🤕

Oh here we go again - the sob story tour. You overdosed? Congrats. Now you get free scans and therapy? What about the guy who lost his job because his kid got sick and he couldn’t afford meds? No one gives him a damn MRI. This is why America’s broke. Everyone wants a handout now. Stop playing the victim. Get a job. Stop blaming the system.

Wow. Just… wow. You’re lucky you’re alive. But honestly? If you’re still alive after an overdose, you probably didn’t try hard enough. People who really want out don’t wake up. They don’t get rescued. They don’t get MRIs. You got saved because someone else cared. Now act like it. Or stop wasting everyone’s time.

I work in a UK ER. We’ve started doing baseline cognitive screens on every overdose survivor now. It’s not perfect - but we’re trying. The biggest thing? People don’t realize how long it takes for damage to show up. One guy came in for a follow-up six months later and couldn’t remember his own address. We found a silent stroke. No one had checked. This isn’t about blame. It’s about seeing the person behind the overdose.