Heart Rate to Exercise Tolerance Calculator

Calculate Your Potential Exercise Improvement

Based on clinical data showing a 1-2 mL·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹ improvement in peak VO₂ for every 5-10 bpm heart rate reduction.

Potential Improvement

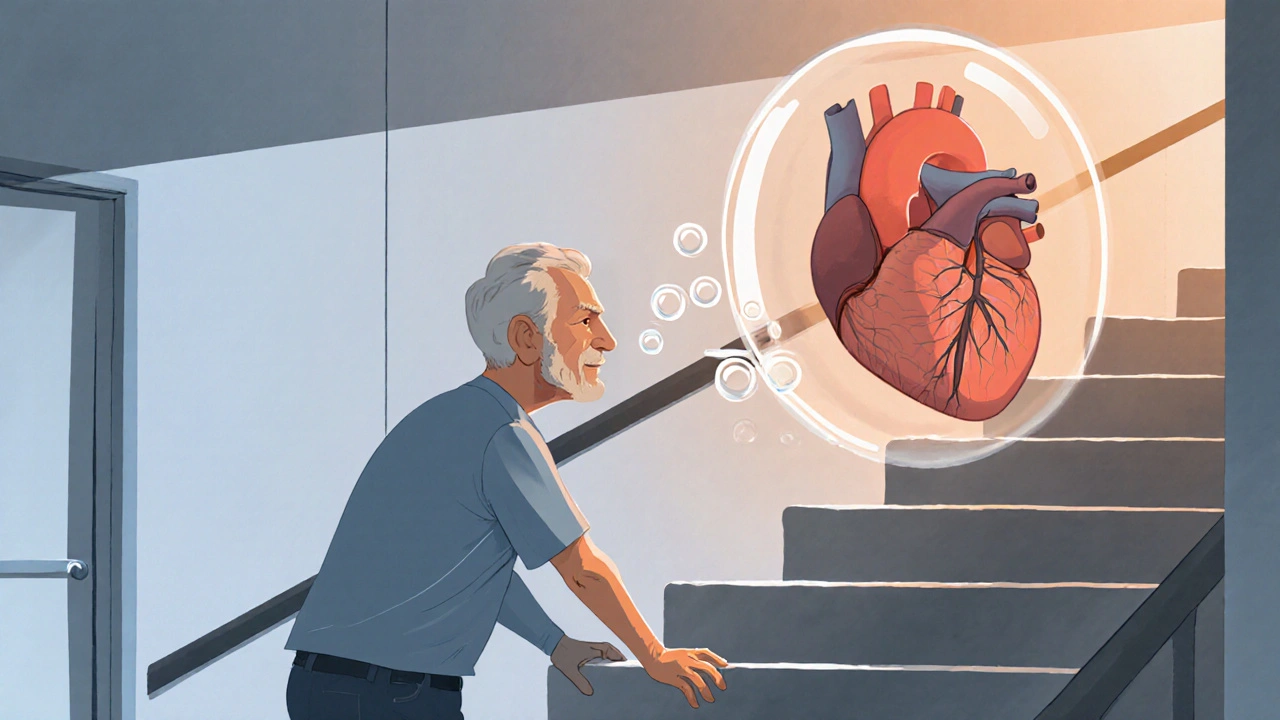

When a patient with heart failure struggles to walk up a flight of stairs, the problem isn’t just a weak heart - it’s a hard‑earned battle between the body’s oxygen needs and a sluggish pump. Ivabradine has emerged as a drug that can ease that fight, but how does it work and what does the data actually say? Below we unpack the science, the trials, and the day‑to‑day decisions that shape whether ivabradine belongs in a heart‑failure regimen.

What Is Ivabradine?

Ivabradine is a selective I_f‑channel inhibitor that lowers heart rate by slowing the spontaneous depolarisation of the sinus node. First approved in Europe in 2005 for chronic angina, it earned a heart‑failure label after the SHIFT trial showed clear mortality benefits for patients with reduced ejection fraction.

Unlike beta‑blockers, ivabradine does not blunt contractility or blood pressure, which makes it an attractive add‑on when those parameters are already optimised.

Why Exercise Tolerance Drops in Heart Failure

Heart Failure is a syndrome where the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body's metabolic demands. The result is a cascade of physiological changes that chip away at exercise capacity.

- Reduced left‑ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) limits stroke volume.

- Neuro‑hormonal activation raises systemic vascular resistance.

- Chronotropic incompetence-an inability to raise heart rate appropriately-curtails cardiac output during activity.

- Skeletal‑muscle abnormalities, including mitochondrial dysfunction, further lower oxygen utilisation.

These factors combine to lower the peak VO₂ (aerobic capacity) and push patients into a higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class with even mild exertion.

How Ivabradine Improves Exercise Tolerance

The drug’s magic lies in its precise targeting of the sino‑atrial (SA) node. By inhibiting the I_f (funny) current, ivabradine reduces resting heart rate by 5‑10 beats per minute without affecting contractility or blood pressure. This modest slowdown gives the ventricles more filling time, which can improve stroke volume in a failing heart.

In practical terms, a lower heart rate means the body needs less oxygen at rest, leaving a larger reserve for physical activity. Studies consistently show a modest rise in peak VO₂-typically 1‑2 mL·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹-when ivabradine is added to guideline‑directed therapy.

Clinical Evidence: From SHIFT to 2024 Meta‑Analyses

The landmark SHIFT trial enrolled 6,558 patients with LVEF ≤35 % and sinus rhythm >70 bpm. Ivabradine reduced the composite of cardiovascular death or heart‑failure hospitalisation by 18 % (HR 0.82, p < 0.001). Sub‑analysis revealed a 12 % improvement in six‑minute walk distance compared with placebo.

Follow‑up studies-such as the BEAUTIFUL trial (focused on coronary disease with left‑ventricular dysfunction) and several real‑world registries-reinforced these findings, showing:

- Greater gains in NYHA class (average improvement of one class).

- Reduced resting heart rate by ~8 bpm, correlating with lower BNP levels.

- Better quality‑of‑life scores on the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire.

A 2023 meta‑analysis of nine randomized trials (≈9,400 participants) confirmed that ivabradine adds ~0.9 mL·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹ to peak VO₂ and cuts heart‑failure hospitalisations by 16 %.

Ivabradine vs. Beta‑Blockers: When to Add One on Top of the Other

Both drug classes lower heart rate, but they do so through different mechanisms. Beta‑blockers blunt sympathetic drive and can lower blood pressure, while ivabradine works exclusively on the SA node without negative inotropy.

| Feature | Ivabradine | Beta‑Blocker |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | I_f‑channel inhibition (SA node) | β‑adrenergic blockade (sympathetic) |

| Effect on Blood Pressure | Neutral | Usually lowers |

| Impact on Contractility | No negative inotropy | Can reduce contractility |

| Ideal Patient Profile | HR ≥ 70 bpm, sinus rhythm, already on max‑tolerated β‑blocker | Elevated sympathetic tone, hypertension |

| Adverse Effects | Bradycardia, visual phosphenes | Fatigue, bronchospasm, hypotension |

Guidelines (2022 ESC) recommend ivabradine as a Class IIa add‑on for patients who remain above 70 bpm despite optimal β‑blocker dose. In practice, many clinicians start with a β‑blocker, titrate to the highest tolerated dose, then consider ivabradine if heart rate is still high and symptoms persist.

Practical Prescribing: Dosing, Monitoring, and Safety

Typical dosing begins at 5 mg twice daily, taken with food. After two weeks, the dose can be uptitrated to 7.5 mg twice daily if the resting heart rate remains >60 bpm and no bradycardic events occur.

Key monitoring points:

- Resting heart rate: target 50‑60 bpm, but never below 50 bpm.

- Electrocardiogram: ensure sinus rhythm; atrial fibrillation contraindicates use.

- Visual disturbances: about 5 % report transient phosphenes; counsel patients to report persistent changes.

- Renal function: dose adjustment not required, but severe impairment warrants caution.

Ivabradine should be discontinued if heart rate falls below 50 bpm or if serious bradyarrhythmia develops.

Real‑World Stories: Turning a “Can't‑Walk‑Far” Patient into a “Can‑Do‑More” One

John, a 62‑year‑old ex‑carpenter from Manchester, was diagnosed with NYHA class III heart failure (LVEF 30 %). Despite being on ACE‑inhibitor, spironolactone, and a maximally tolerated bisoprolol, his resting HR lingered at 78 bpm and he could barely walk 300 m on a six‑minute walk test.

After adding ivabradine 5 mg twice daily, his HR dropped to 66 bpm within ten days. Six weeks later, his six‑minute walk distance rose to 460 m, and he reported being able to climb two flights of stairs without stopping. BNP fell from 850 pg/mL to 420 pg/mL, reinforcing the physiological benefit.

John’s case mirrors the trial data: a modest heart‑rate reduction translates into tangible functional gains, especially when baseline exercise capacity is severely limited.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is eligible for ivabradine therapy?

Patients with chronic heart failure (LVEF ≤ 35 %), sinus rhythm, resting heart rate ≥ 70 bpm, and who are already on maximally tolerated β‑blocker therapy are the primary group. The drug is not indicated for atrial fibrillation, acute decompensation, or severe hypotension.

Can ivabradine replace beta‑blockers?

No. Ivabradine is an add‑on, not a substitute. Beta‑blockers address sympathetic over‑activity and have mortality benefits independent of heart‑rate control. Ivabradine only targets the SA node and does not provide the full neuro‑hormonal blockade that beta‑blockers do.

What are the most common side effects?

The two most frequently reported adverse events are symptomatic bradycardia and transient visual disturbances (phosphenes). Both are usually reversible on dose adjustment or discontinuation.

How quickly does exercise tolerance improve?

Improvements can be seen as early as four weeks, with peak benefits typically occurring between eight and twelve weeks of stable dosing. Ongoing monitoring of heart rate and functional capacity helps gauge response.

Is ivabradine safe for patients with renal impairment?

The drug is largely eliminated unchanged via the liver, so no dose reduction is required for mild‑to‑moderate renal dysfunction. However, severe renal failure warrants careful clinical judgement and close monitoring.

Bottom line: ivabradine can be a game‑changer for heart‑failure patients stuck in a low‑exercise‑tolerance loop, but it works best when paired with a solid foundation of guideline‑directed therapy and careful patient selection.

Comments

Man, ivabradine is like the unsung hero in the HF saga – it sneaks in, chills the sinus node and lets the ventricles fill up like a lazy river. No beta‑blocker drama, just pure heart‑rate trimming without crushing contractility. The SHIFT data shows a neat 5‑10 bpm dip, and that translates into a few extra meters on the 6‑minute walk – pure gold for anyone stuck at the bottom of the stairs. It’s wild how a modest HR drop can free up oxygen reserves for the muscles, kinda like turning down the thermostat so the engine doesn’t overheat while you’re climbing. Plus, the side‑effect profile is chill – just watch out for those fleeting light‑show phosphenes. In short, ivabradine is the quiet ninja that steps in when beta‑blockers have hit their max and the patient still paces around at 80‑plus bpm.

Honestly i cant beleive how many doc's in other countrys ignore this drug while we in the US have access to the best protocols. Ivabradine is part of the top tier of treatment and if your doc wont prescribe it maybe they aren't up to date or just lazy. The trial data is crystal clear and the guidelines say it’s a class IIa add‑on – so if your heart rate is still high after max beta blocker you should be on it. Stop making excuses and get the right care!

Everyone talks about ivabradine like it's a miracle pill but have you ever wondered why pharma pushes it so hard? They love a drug that can be sold as a niche add‑on while keeping the main beta‑blocker market intact. Plus, the side‑effects are downplayed – those visual flashes could be a sign of something deeper. I suspect the data we see is filtered through corporate lenses, and the real long‑term safety is still hidden. Keep your eyes open, people.

Ivabradine works by selectively inhibiting the funny current (If) in the sino‑atrial node which reduces spontaneous depolarisation. This lowers resting heart rate without affecting myocardial contractility or systemic vascular resistance. The result is increased diastolic filling time which can modestly improve stroke volume in a failing heart. Clinical trials such as SHIFT have demonstrated reductions in cardiovascular death and HF hospitalisations. The drug is indicated for patients in sinus rhythm with HR ≥70 bpm despite optimal beta‑blocker therapy. It must be avoided in atrial fibrillation because the mechanism relies on sinus node activity. Dosing starts at 5 mg twice daily and can be uptitrated based on heart‑rate response. Monitoring includes resting HR, ECG for rhythm, and vigilance for bradycardia or visual disturbances. Overall, it’s a valuable add‑on when used in the right patient population.

Wow, another miracle drug, because we definitely needed more pills for heart failures.

😂 Absolutely! It’s great to see the community sharing insights – every perspective helps us all learn more about managing HF wisely. 🌟 Keep the info coming! 🙌

For anyone hesitating, think of ivabradine as a subtle tune‑up for the heart’s pacing. It won’t replace beta‑blockers, but it can lift a patient out of that dreaded NYHA III slump. Start low, watch the heart‑rate, and celebrate each extra step on the walking test. Consistency and proper monitoring are key – the payoff is real functional gain.

Sounds promising! :) How soon can someone expect to feel a difference?

Ivabradine’s pharmacodynamic profile is characterised by a dose‑dependent reduction in sinus node automaticity via selective inhibition of the hyperpolarisation‑activated cyclic nucleotide‑gated (HCN) channels, specifically the I_f current. This mechanistic action decouples heart‑rate control from β‑adrenergic pathways, thereby preserving inotropy and arterial pressure homeostasis. In the pivotal SHIFT trial, a mean reduction of 8 beats per minute was associated with a statistically significant 18 % relative risk reduction in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart‑failure hospitalization (hazard ratio 0.82, p < 0.001). Sub‑analyses further demonstrated an incremental improvement in six‑minute walk distance averaging 35 meters, which correlates with enhanced peak VO₂ values of approximately 0.9 mL·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹. Meta‑analytic synthesis of nine randomized controlled trials encompassing roughly 9,400 participants reinforces these findings, revealing consistency across diverse geographic cohorts and baseline beta‑blocker uptitration statuses. Importantly, the safety signal remains favourable; the incidence of symptomatic bradycardia (<50 bpm) was observed in 4.5 % of patients, while transient luminous phenomena (phosphenes) occurred in 5.2 % and were reversible upon dose modification. Renal clearance is negligible, with hepatic metabolism via CYP3A4 predominating, obviating the need for dose adjustment in mild‑to‑moderate renal impairment. Clinical guidelines therefore endorse ivabradine as a Class IIa recommendation for patients with left‑ventricular ejection fraction ≤35 %, sinus rhythm, and resting heart rate ≥70 bpm despite maximally tolerated β‑blocker therapy. Pragmatic implementation mandates baseline electrocardiographic confirmation of sinus rhythm, exclusion of atrial fibrillation, and vigilant heart‑rate surveillance post‑initiation, typically commencing at 5 mg twice daily with potential escalation to 7.5 mg twice daily contingent upon heart‑rate response and tolerability. In summary, ivabradine provides a mechanistically distinct, evidence‑based adjunct that synergistically enhances haemodynamic efficiency, attenuates adverse remodeling signals, and improves patient‑centred functional outcomes when integrated within comprehensive guideline‑directed medical therapy.