When your bones start hurting for no obvious reason, it can be hard to know whether it’s a metabolic issue like osteodystrophy or something more serious like a bone tumor. Both conditions affect the skeleton, but they arise from very different mechanisms and need distinct approaches. This guide breaks down the key causes, warning signs, and current treatment options so you can spot red flags early and understand what doctors might recommend.

Quick Take

- Osteodystrophy usually stems from hormonal or metabolic imbalances; bone tumors are abnormal cell growths.

- Common symptoms overlap (pain, swelling, fractures), but tumors often cause rapid, localized pain.

- Blood tests, X‑rays, CT/MRI, and biopsies are the main tools for diagnosis.

- Treatment for osteodystrophy focuses on correcting the underlying metabolic defect; bone tumors may require surgery, chemo, or radiation.

- Any unexplained bone pain lasting more than a few weeks warrants a medical evaluation.

What Is Osteodystrophy?

Osteodystrophy is a broad term for bone disorders caused by abnormal mineral metabolism, hormonal imbalance, or chronic disease. The condition covers several subtypes, the most common being renal osteodystrophy, which occurs in people with chronic kidney disease, and hypophosphatemic osteodystrophy, linked to low phosphate levels.

Key causes include:

- Chronic kidney disease leading to impaired activation of vitamin D and calcium‑phosphate dysregulation.

- Hyperparathyroidism, where excess parathyroid hormone (PTH) pulls calcium from bones.

- Vitamin D deficiency, reducing calcium absorption.

- Genetic mutations affecting phosphate transport.

Typical symptoms are often subtle at first:

- Bone pain, especially in the spine, ribs, and long bones.

- Muscle weakness and fatigue.

- Frequent fractures with minimal trauma.

- Growth retardation in children.

Doctors usually start with blood tests (calcium, phosphate, PTH, vitamin D levels) and imaging such as X‑ray or dual‑energy X‑ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to assess bone density. A definitive diagnosis may require a bone biopsy, especially when the cause is unclear.

Treatment approach aims to correct the metabolic disturbance:

- Supplemental calcium and active vitamin D (calcitriol) for patients with low levels.

- Phosphate binders for those with hyperphosphatemia.

- Surgical removal of overactive parathyroid glands (parathyroidectomy) in severe hyperparathyroidism.

- Regular monitoring of bone density and laboratory values.

What Are Bone Tumors?

Bone tumor is a growth of abnormal cells within bone tissue; it can be benign (non‑cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Primary bone cancers are rare, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers, but metastases from cancers such as breast, lung, and prostate frequently involve bone.

Classification:

- Osteosarcoma - a high‑grade malignant tumor most common in teenagers.

- Ewing sarcoma - primarily affects children and young adults.

- Benign lesions like osteochondroma and enchondroma.

- Metastatic bone disease, where cancer from other organs spreads to bone.

Common causes include genetic mutations (e.g., TP53, RB1), radiation exposure, and, for metastatic lesions, the primary cancer’s biology.

Symptoms can be more aggressive than those of osteodystrophy:

- Constant, deep‑seated pain that worsens at night.

- Visible swelling or a palpable mass.

- Pathological fractures - breaks that occur with minimal force.

- Systemic signs such as weight loss or fever in malignant cases.

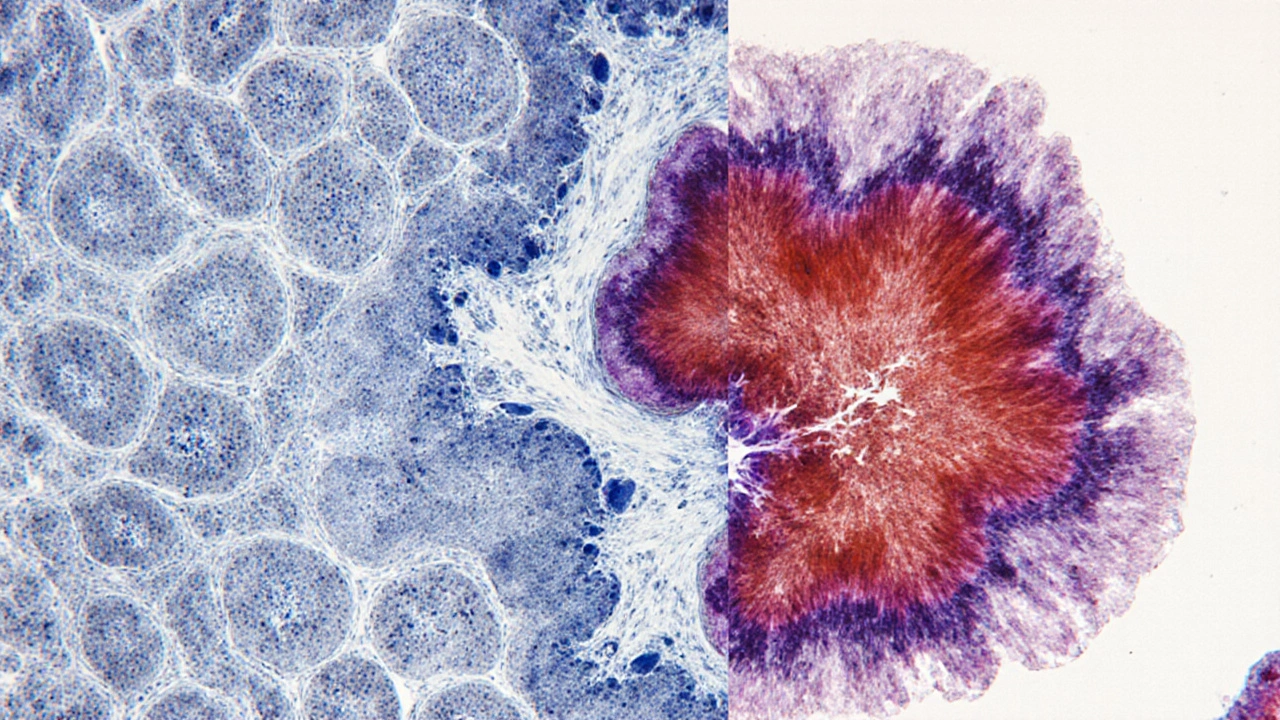

Diagnostic work‑up typically begins with plain radiographs, followed by MRI or CT to delineate the lesion’s extent. A definitive diagnosis relies on a core needle biopsy examined by a pathologist.

Treatment strategies vary with tumor type and stage:

- Surgical resection with clean margins - the cornerstone for most primary bone tumors.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy for high‑grade sarcomas (e.g., osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma).

- Radiation therapy for inoperable tumors or to shrink metastatic lesions.

- Targeted therapies and immunotherapy for specific metastatic cancers (e.g., denosumab for bone‑dominant breast cancer).

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Feature | Osteodystrophy | Bone Tumor |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Metabolic/hormonal imbalance (e.g., kidney disease, hyperparathyroidism) | Abnormal cell proliferation (primary sarcoma or metastasis) |

| Common age group | Adults with chronic disease; children with genetic forms | Teens for osteosarcoma; adults for metastases |

| Typical pain pattern | Dull, activity‑related, improves with rest | Persistent, night‑worsening, often severe |

| Diagnostic hallmark | Abnormal labs (Ca, P, PTH) + low bone density | Radiographic lesion + histologic confirmation |

| First‑line treatment | Correct underlying metabolic defect | Surgical removal ± chemotherapy/radiation |

When Symptoms Overlap - How to Tell What’s Going On

Both conditions can cause bone pain and fractures, which makes self‑diagnosis tricky. A few practical tips can help you decide when to push for urgent care:

- If pain is localized to one spot, worsening at night, and accompanied by swelling, think tumor.

- If pain is more diffuse, linked to a known chronic illness (e.g., kidney disease), and lab tests show calcium/phosphate anomalies, osteodystrophy is more likely.

- Any sudden fracture without major trauma should raise suspicion for an underlying lesion.

- Persistent symptoms for more than four weeks despite standard pain relief merit imaging.

Never wait for the pain to “go away” on its own. Early imaging can differentiate a harmless metabolic change from a potentially life‑threatening neoplasm.

Treatment Options in Depth

Below is a concise checklist for patients and caregivers navigating treatment decisions.

- Medical management - calcium, vitamin D, phosphate binders, and hormone modulators for osteodystrophy.

- Surgical intervention - curettage, wide excision, or limb‑sparing surgery for bone tumors.

- Systemic therapy - chemotherapy protocols (e.g., methotrexate, doxorubicin) for sarcomas; targeted agents for metastatic cancers.

- Radiation - external beam radiation for inoperable tumors or to control pain from metastases.

- Rehabilitation - physiotherapy to restore function after fracture or surgery.

- Follow‑up monitoring - repeat imaging every 3‑6 months for tumor patients; DEXA scans annually for osteodystrophy.

Lifestyle tweaks can also support recovery: weight‑bearing exercise (as tolerated), balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D, and smoking cessation to improve bone health.

Next Steps and When to Seek Help

If you notice any of the warning signs listed above, schedule an appointment with your GP or a specialist in orthopaedics/endocrinology. Bring a list of current medications, recent lab results, and a clear description of your pain pattern. Early referral to a radiologist for imaging can dramatically alter outcomes, especially for malignant bone tumors.

Remember, while osteodystrophy is often manageable with medication, bone tumors may require aggressive multi‑disciplinary care. Acting quickly can preserve both bone function and overall health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can osteodystrophy turn into a bone tumor?

No. Osteodystrophy is a metabolic disorder, whereas bone tumors are caused by abnormal cell growth. However, chronic bone weakening can make fractures more likely, which sometimes leads doctors to investigate further.

What imaging test is best for distinguishing the two conditions?

A plain X‑ray is the first step for both. MRI or CT provides detailed soft‑tissue contrast for tumors, while bone density scans (DEXA) assess metabolic bone loss typical of osteodystrophy.

Is surgery ever needed for osteodystrophy?

Surgery is rare and only considered for severe complications, such as correcting deformities after multiple fractures. Primary treatment focuses on medical correction of the underlying imbalance.

How long does chemotherapy last for osteosarcoma?

Typical regimens run for 6‑12 months, combining pre‑operative (neoadjuvant) and post‑operative (adjuvant) cycles. The exact schedule depends on tumor response and patient tolerance.

Can lifestyle changes reverse osteodystrophy?

Lifestyle alone cannot correct the biochemical drivers, but adequate calcium/vitamin D intake, regular weight‑bearing activity, and quitting smoking greatly improve bone density and reduce fracture risk when combined with proper medical therapy.

Comments

Yeah, because bones love drama as much as my inbox.

This guide really breaks down the nitty‑ gritty of bone health. I love how it separates metabolic stuff from tumors, because that’s where most of us get confused. The symptom checklist is spot on – especially the night‑time pain tip. Also, the reminder to get labs early could save a lot of unnecessary suffering. Thanks for the clear, actionable steps.

Listen, the "official" medical narrative is just a front, a smoke screen, for the real agenda, a hidden agenda, that seeks to keep us ignorant, and the facts are being suppressed, by those in power, who don’t want us to know the truth about bone disease, and the vaccines, they’re all connected, don’t be fooled.

Totally agree with the point about early labs. When you catch a calcium or PTH imbalance early, you can tweak diet and meds before it spirals. It also saves a lot of anxiety for patients who fear the worst. Staying proactive is the best strategy.

Everyone needs to wake up – the pharma‑industry is hiding the link between micro‑chips and bone degeneration. They’re injecting chemicals that mess with our metabolism, making us vulnerable to osteodystrophy while they sell “miracle” cancer cures. Trust no one who says it’s just a vitamin deficiency.

Reading through the table, the first thing that struck me was how often patients overlook the subtle cues that their bodies are trying to convey. Bone pain that eases with activity can be dismissed as a muscle strain, yet it may be the early whisper of an underlying metabolic imbalance. In my experience, those who keep a symptom diary notice patterns that clinicians might miss in a rushed appointment. For example, documenting the time of day when pain peaks can point toward a tumor, because malignant lesions often intensify at night. Conversely, a diffuse ache that improves after a warm shower may hint at osteodystrophy, especially if the patient has chronic kidney disease. It is also crucial to integrate lab trends with imaging; a rising PTH level accompanied by a subtle loss of bone density on DEXA should raise alarms. Moreover, the psychological impact of chronic bone pain cannot be overstated – patients often develop anxiety, which can exacerbate perceived pain. Providing them with coping strategies, such as guided breathing and gentle stretching, can improve outcomes. Nutrition plays a pivotal role; adequate calcium and vitamin D intake should be tailored to individual absorption capacities. In renal osteodystrophy, phosphate binders become a cornerstone, but they must be balanced against the risk of vascular calcification. Surgical options, though rarely needed for osteodystrophy, become lifesaving when fractures lead to deformities that impair mobility. For bone tumors, early multidisciplinary involvement is key – orthopedic oncologists, radiologists, and medical oncologists must coordinate treatment plans. Limb‑sparing surgeries have advanced dramatically, offering patients better functional recovery than amputation. Yet, chemotherapy regimens remain intense, and patients should be counseled about potential side effects, such as cardiotoxicity. Finally, follow‑up schedules should be individualized; some patients benefit from quarterly imaging, while others may need annual scans. The overarching message is clear: a collaborative, patient‑centered approach yields the best chances for preserving both bone health and quality of life.

The article is thorough yet overly simplistic in places, missing the nuanced interplay of endocrine pathways that truly drive osteodystrophy.

Great deep dive, Marcella! 🌟 Adding to that, when dealing with metastatic bone disease, bone‑stabilizing agents like denosumab can really cut down on skeletal‑related events. Also, don’t forget that patients on long‑term steroids need prophylactic calcium and vitamin D to mitigate secondary osteoporosis. Keep the interdisciplinary team in loop!

Honestly, if you’re not proud of our country's medical research, why are you even reading this? We have the best bone specialists, period.

Look, the jargon in oncology is intentionally obfuscating. They hide the fact that many so‑called “targeted therapies” are just placebo vectors. The whole system thrives on our confusion, and the hype around sarcomas is just a cash‑grab.

Do you really think the imaging tech is neutral? Those machines are calibrated by the same agencies that control the data flow on bone health, ensuring we never see the real picture of synthetic bone‑growth experiments.

Honestly, the “quick take” list is fine but it skips over the cost‑benefit analysis of chemo versus limb‑sparing surgery. Patients need to know the financial toxicity too.

While you’re all talking about treatments, nobody mentions the hidden side‑effects of the pharma‑driven protocols. They often push aggressive chemo without informing patients about the long‑term marrow suppression risks.

From a philosophical standpoint, the dichotomy between metabolic and neoplastic bone disease reflects the larger conflict between nature and technology; we must reconcile them through integrative medicine.

Interesting read; the balance between surgical and medical management is indeed a cultural touchstone in orthopaedic practice across regions.

Thank you for the comprehensive checklist; I would add that regular monitoring of serum alkaline phosphatase can also aid in differentiating between osteodystrophy and tumor activity.

Love the guide! :) Just a heads‑up, many patients benefit from early physiotherapy to maintain mobility while they’re undergoing treatment.

Wow, the detail is impressive, but let’s be real – most people will just skim and miss the crucial warning signs about night‑time pain.

Good points overall; just ensure that any medical advice is checked for grammar and clarity before publishing, as precise language prevents misinterpretation.