When it comes to kidney disease, not everyone faces the same risk. For people with recent African ancestry, one gene - APOL1 a gene that influences kidney cell function and immune response - plays a massive role. It doesn’t affect everyone, but for those who carry two copies of certain variants, the chance of developing serious kidney disease jumps dramatically. This isn’t about race. It’s about ancestry. And it’s one of the clearest examples we have of how evolution can leave behind unintended health consequences.

Why APOL1 Exists: A Survival Advantage Gone Wrong

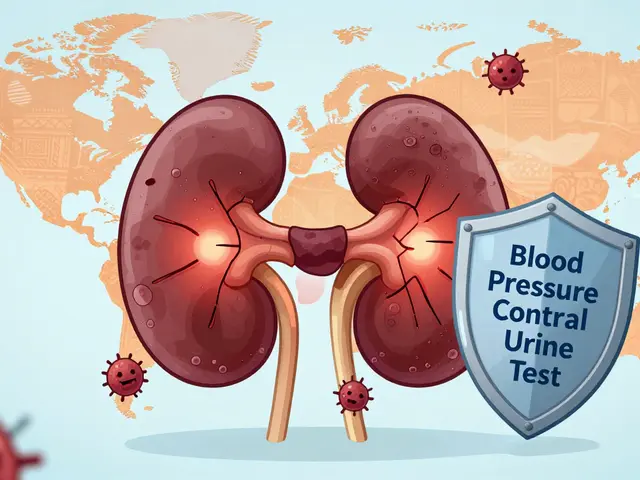

Thousands of years ago, in West and Central Africa, a deadly parasite called Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense caused African sleeping sickness. It killed quickly. But some people carried mutations in the APOL1 gene that helped their bodies destroy the parasite. These mutations - called G1 and G2 - gave them a huge survival edge. They lived longer. They had more children. And over generations, these gene variants became common in populations from that region.

Fast forward to today. The parasite is mostly gone in many areas. But the APOL1 variants didn’t disappear. They traveled with people during the transatlantic slave trade and spread across the Americas and the Caribbean. Now, about 30% of people with recent West African ancestry carry at least one of these variants. And about 13% of African Americans have two copies - the high-risk combination.

How APOL1 Causes Kidney Damage

The APOL1 gene makes a protein that normally attacks trypanosomes by poking holes in their membranes. But in kidney cells, the same protein can go rogue. When two risky variants are present - either G1/G1, G2/G2, or G1/G2 - the protein becomes toxic. It starts damaging the filtering units of the kidney, called glomeruli. This leads to scarring, protein leakage into urine, and eventually, kidney failure.

The diseases most often linked to APOL1 variants are:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS)

- Collapsing glomerulopathy

- HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN)

- Hypertensive kidney disease (in people with high blood pressure)

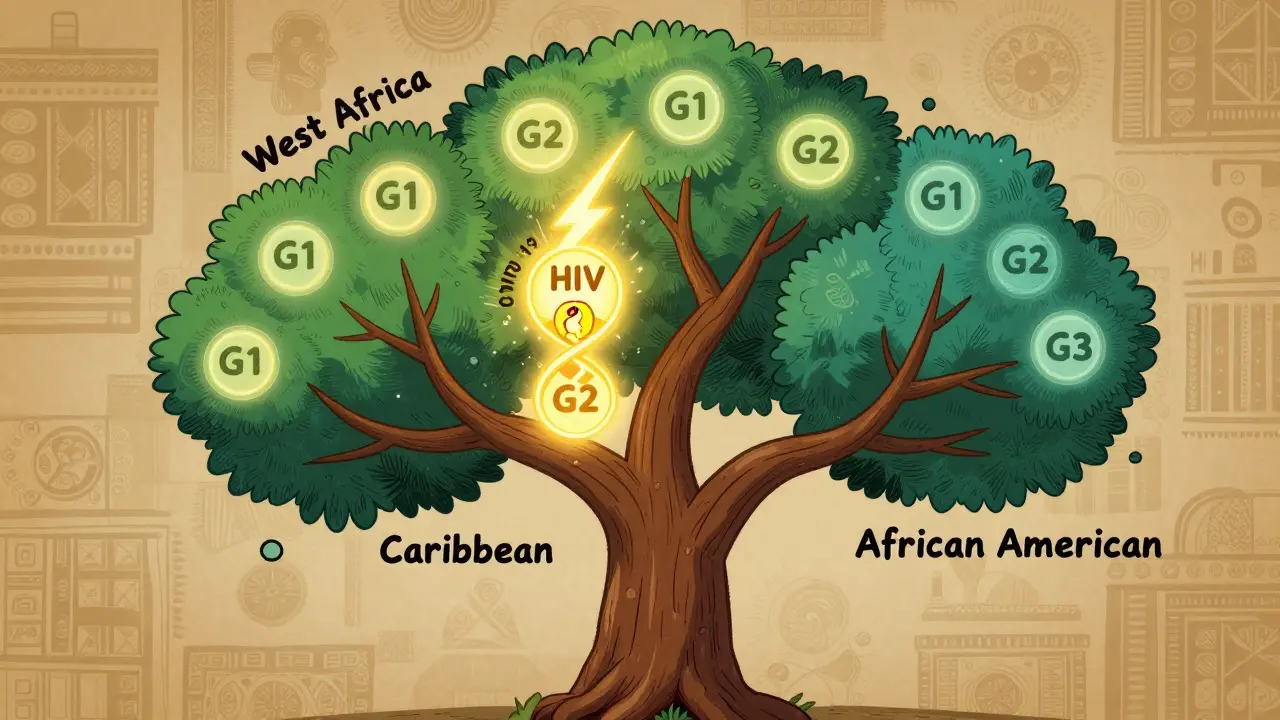

Here’s the twist: Most people with two risky APOL1 variants never develop kidney disease. Studies show only about 15-20% of them will. That means 80% carry the risk but stay healthy. Why? Because something else - a "second hit" - usually triggers the damage. That could be:

- HIV infection

- COVID-19

- Severe stress or illness

- High blood pressure

- Obesity

- Some medications

That’s why someone might live a long life with APOL1 risk and never have a problem - until they get sick, or their blood pressure climbs unchecked.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

The impact of APOL1 on kidney disease disparities is staggering. African Americans are 3 to 4 times more likely to develop kidney failure than white Americans. APOL1 explains about 70% of that difference. Among African Americans with non-diabetic kidney disease, nearly half have high-risk APOL1 genotypes. In people with HIV and kidney failure of African ancestry, almost half of the cases are directly tied to APOL1.

And it’s not just in the U.S. Studies from the UK, Brazil, and Nigeria show the same pattern. In Ghana and Nigeria, up to 30% of people carry at least one risky variant. But if you’re of European, Asian, or Indigenous American ancestry, these variants are virtually nonexistent. That’s why APOL1-related kidney disease is almost exclusive to people with recent African ancestry.

Testing for APOL1: Who Should Get It?

APOL1 genetic testing has been available since 2016. It’s a simple blood or saliva test. But it’s not for everyone. Right now, testing is recommended for:

- People of African ancestry with unexplained kidney disease (especially FSGS or collapsing glomerulopathy)

- Living kidney donors with African ancestry - to protect them from future kidney risk

- People with HIV and kidney problems

- Those with a strong family history of kidney failure

The test costs between $250 and $450 without insurance. Some insurers cover it if there’s clear medical reason. Results usually come back in 1 to 2 weeks.

But here’s the catch: Many doctors don’t know how to interpret the results. A 2022 survey found that 78% of nephrologists felt underprepared to explain APOL1 risk to patients. And many patients misunderstand the numbers. They think "high-risk" means they will definitely get kidney disease. It doesn’t. It means their risk is higher - and they need to be extra careful.

What You Can Do If You Have High-Risk APOL1

There’s no cure yet. But there are proven ways to reduce your risk:

- Control blood pressure. Keep it below 130/80 mmHg. ACE inhibitors or ARBs are often used - they protect the kidneys even if you don’t have high blood pressure.

- Check your urine yearly. A simple urine test for albumin (protein) can catch early kidney damage before it’s too late.

- Avoid NSAIDs. Ibuprofen, naproxen, and similar painkillers can hurt kidneys, especially with APOL1 risk.

- Manage weight and diabetes. Even if you don’t have diabetes, excess weight strains the kidneys.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking speeds up kidney damage.

- Get vaccinated. Stay up to date on flu, COVID-19, and pneumonia shots. Infections are common "second hits."

Some people with APOL1 risk have gone decades without issues - because they stayed vigilant. One woman, Emani, found out she had high-risk APOL1 during a routine checkup. She started monitoring her blood pressure and urine every year. Five years later, her kidney function is still normal. "Knowing gave me power," she said.

The Bigger Picture: Race, Ancestry, and Medicine

It’s easy to misread APOL1 as a "Black disease." But that’s wrong. It’s not about race. It’s about ancestry. Someone with West African ancestry - whether they live in Nigeria, Jamaica, or Atlanta - has the risk. Someone with no African ancestry doesn’t, no matter their skin color.

This distinction matters. In the past, doctors used race to adjust kidney function estimates (eGFR). Black patients were automatically given higher numbers, delaying diagnosis. Now, the American Society of Nephrology and the FDA have moved away from race-based calculations. APOL1 testing is replacing guesswork with precision.

As Dr. Olugbenga Gbadegesin put it: "We must separate biology from social constructs." APOL1 isn’t a Black problem. It’s a genetic one - and it affects people with specific ancestry, no matter where they live.

What’s Next? New Treatments on the Horizon

For years, there was no treatment targeting APOL1 directly. That’s changing. Vertex Pharmaceuticals is testing a drug called VX-147, designed to block the toxic APOL1 protein. In a 2023 trial, patients on VX-147 saw a 37% drop in proteinuria in just 13 weeks. That’s a big deal - less protein in urine means less kidney damage.

The NIH has launched a 10-year study tracking 5,000 people with APOL1 risk to better understand what triggers disease. And by 2026, new screening guidelines are expected to recommend routine APOL1 testing for people of African ancestry with high blood pressure or protein in their urine.

By 2035, experts believe APOL1-targeted therapies could reduce kidney failure rates in this population by 25-35%. But only if access is fair. Right now, only 12% of low- and middle-income countries offer APOL1 testing. That’s a global health gap that needs fixing.

Final Thoughts

APOL1 isn’t a death sentence. It’s a warning sign. A genetic red flag that tells you to pay closer attention to your kidneys. For many, it’s the missing piece in understanding why their kidneys failed when others’ didn’t. For others, it’s motivation to take control - through monitoring, lifestyle, and early intervention.

The science is clear: APOL1 variants explain most of the kidney disease gap between African Americans and white Americans. But the solution isn’t just in the lab. It’s in awareness, access, and action. Know your risk. Monitor your health. Talk to your doctor. And don’t let fear stop you from taking charge - because knowledge, in this case, really can save your kidneys.

Is APOL1 testing covered by insurance?

It depends. Many insurers cover APOL1 testing if you have unexplained kidney disease, are a living kidney donor with African ancestry, or have HIV-related kidney damage. If you’re testing for personal curiosity without a medical reason, it’s usually not covered. Costs range from $250 to $450 out-of-pocket. Always check with your provider before testing.

Can I get APOL1 tested if I don’t have kidney problems?

Yes - but only under certain conditions. If you’re a person of African ancestry and you’re considering becoming a living kidney donor, testing is strongly recommended. Some doctors also offer testing to people with high blood pressure or protein in urine, even if kidney function is normal. For healthy people with no symptoms, routine testing isn’t yet standard. Talk to a nephrologist or genetic counselor first.

If I have two APOL1 risk variants, will I definitely get kidney disease?

No. Only about 15-20% of people with two risky variants develop kidney disease. The rest live with the genetic risk but never have symptoms. What triggers disease in those who do? Often, a "second hit" - like HIV, uncontrolled high blood pressure, or a severe infection. That’s why managing those factors is so important.

Why is APOL1 risk only found in people of African ancestry?

The G1 and G2 variants evolved in West and Central Africa as a defense against African sleeping sickness. Natural selection favored people who carried them because they survived longer. These variants spread through populations with African ancestry but are extremely rare in other groups. That’s why you won’t find them in people of European, Asian, or Indigenous American descent - they never developed or needed these mutations.

Are there any drugs to treat APOL1-related kidney disease?

Not yet approved, but close. Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ drug VX-147 showed strong results in a 2023 trial, reducing proteinuria by 37% in 13 weeks. It’s expected to apply for FDA approval by 2025. Until then, standard treatments - blood pressure control with ACE inhibitors/ARBs, avoiding NSAIDs, and managing weight - remain the best tools to slow progression.